On this month's Special Page

An interview with the World Horror Convention Grand Master Award winner Ray Garton

IN THE "SPECIAL PAGE" ARCHIVES:

Jonathan Maberry

Trish Wilson

J.G.Faherty

Nancy Kilpatrick

Joe R. Lansdale

Christian A. Larsen

Marc Ciccarone

Mylo Carbia

Trish Wilson interviews Ray Garton for The Horror Zine

TRISH WILSON: You grew up in a Seventh Day Adventist household. How did that experience influence your interest in horror?

RAY GARTON: Immensely. It created my interest in horror. When people ask why I write horror fiction, I always say it’s because I was raised a Seventh-day Adventist. And that’s true. I was a terrified child, afraid of my own shadow, because that’s all the church is—fear. It’s a doomsday cult—the Adventist church has done a good job of convincing everyone that it’s a mainstream Christian religion, but it’s not, it’s a pseudo-Christian cult with beliefs that are heretical to traditional Christianity—and I grew up in fear of the Last Days. Well, the Last Days and my father; it was an extremely dysfunctional household. The first time I saw a horror movie on TV was a revelation. It was William Castle’s 13 Ghosts, and it scared the hell out of me. But compared to what I was used to, what I lived with, it was a fun kind of scared.

I was about four or five years old at the time, and I distinctly remembering noticing the difference. The ghosts in the movie were terrifying—but at least they weren’t the Last Days, the Time of Trouble, when, as Adventists teach their small children, all the “Sunday-keepers,” led by the evil Catholic church, will pass a Sunday law requiring everyone to worship on Sunday. When Adventists refuse (they worship on Saturday because they have real trouble distinguishing Christianity from Judaism), they will be hunted, imprisoned, tortured, and killed. And it could happen at any time. No wonder I came to pieces every time a TV show was interrupted by a special news bulletin—I was afraid it was going to announce the passage of the Sunday law, in which case it would be time to flee to the hills before the papists could snatch us up and drag us into prison. Everyone in my life was a Seventh-day Adventist, so everyone believed this. There was no one saying anything different, no one questioning or criticizing what we believed. I was a little child, so naturally I believed it, too. But it literally kept me awake nights. Those are horrible things to teach children. I grew up in fear, so fear is an emotion I know well. I took to the horror genre immediately—as a refuge!

TRISH WILSON: When did you first consider yourself to be a writer?

RAY GARTON: Well, in my day (said the old man) you weren’t a writer until you were published. There was no such thing as self-publishing, so being published meant submitting your work, waiting to learn if it was going to be accepted or rejected, dealing with editors, with criticism. I did not call myself a writer until I was published. Before that, I was someone who wrote, someone who wanted to be a writer.

Now, all you need to be a writer is an Amazon account and a website. You might not be able to string a sentence together or tell a coherent story, but you’ve got a book with your name on the cover, so you must be a writer, right? A lot of talented, conscientious writers self-publish, but there are even more people doing it who—honestly, I don’t think some of them have even read a book. They come unglued at the slightest criticism, no matter how constructive, because they’ve never had to deal with rejection or a critical editor. But we’re not supposed to say things like that out loud, so let’s pretend I didn’t.

TRISH WILSON: What kind of music do you like to listen to? Do you listen to music while you write?

RAY GARTON: I listen to jazz, classical, rock and roll, depending on my mood. I frequently listen to music while writing, artists like Jean Michel Jarre, Tangerine Dream, Mike Oldfield, and I listen to a lot of atmospheric movie soundtracks while working, too.

TRISH WILSON: What do you like best about writing?

RAY GARTON: I like the fact that every project is different and brings new problems of its own to solve. It’s not a monotonous occupation. I’m always learning something new about it, always running into new obstacles. It’s an occupation that keeps you alert. As long as you’re writing every day, thinking creatively every day, then that’s all you do, even when you’re not working. Everything becomes possible material for a book or story. And every time I start a new book, it’s a new adventure.

TRISH WILSON: What are some negative aspects of writing that you wish you could change?

RAY GARTON: I’m not crazy about the business end of it. This is the era of DIY promotion, and I’ve never warmed up to that.

TRISH WILSON: You described "In A Dark Place: The Story of a True Haunting" as a low point of your career. Could you go into more detail about the fraud perpetrated by Ed and Lorraine Warren and Al and Carmen Snedeker? Despite your warnings and the warnings of others like CSICOP's Joe Nickel, why do the Warrens continue to have such a strong following due to movies like the "Conjuring" and "Annabelle" series?

RAY GARTON: I used to call it a following, but now I refer to it as the Warren cult. No amount of factual refutation of the Warrens’ work would sway the cultists. You could show them video of Ed Warren telling me to “make it up and make it scary” and their only response would be to viciously attack you, which is exactly what they do. They’ve done it to me plenty of times. They are a nasty, mean-spirited group.

The movies about the Warrens are popular because horror movies are popular. Of the people I know, most know better than to put any stock in a horror movie that starts out with “Based on a true story.” People like them because they find them entertaining and scary. Those are not followers of the Warrens. If those movies were released as fiction—which is what they are, of course— I think they would still be successful. The Warren cult is a different group. They’re the people who attended their lectures, visited their museum of Halloween decorations, and they believe because they want to. Desperately. The people Ed and Lorraine attracted were people a lot like them. Ed was always ready to punch anybody who questioned anything he said, and Lorraine was a mean-spirited woman who spoke hatefully of anyone who didn’t believe every word they said. They were not the pious people they claimed to be. They were foul-mouthed, mean-spirited, opportunistic hucksters. Let’s not forget that they took an underage girl into their home so Ed could have sex with her. He would take her to school in the mornings and drop her off. They were always hiding behind the Catholic religion—which officially wanted nothing to do with them, all the priests they worked with were mostly defrocked, they weren’t affiliated with the church—but there wasn’t a Christlike bone in their bodies.

It was the lowest point in my career because my name was on a book that was fiction but was labeled as nonfiction. That’s what bothered me. After Ed told me to make it up, I knew I was dealing with frauds. But I’d already signed the contract and I couldn’t afford the legal representation it would take to get out of it. The only reason the book is in print again is that I insisted all references to it being a true story be removed from the book. That did not bother Lorraine, and it didn’t bother the Snedekers, all they were interested in was making money. My story hasn’t changed in the decades that I’ve been telling it, but not only has Carmen Snedeker (now Reed) changed her story, she’s telling people she’s some kind of psychic, that she’s a healer. She’s trying to work up a following with the most laughable, semiliterate nonsense you can imagine. She’s now disowned my book because she says I made it all up. That’s not true. I only had to make up the parts of the story that didn’t work. Everything else came from them, mostly from Carmen. But thanks largely to the Warrens, there’s now an entire paranormal industry filled with people like Ed and Lorraine and Carmen, with ghost hunters and psychic investigators. The industry preys on sad people who’ve lost loved ones and it promotes ridiculous beliefs, and it’s growing bigger all the time.

I think the Warrens have contributed greatly to the fact that people now ask me, quite seriously, questions like, “Do you believe in werewolves?” They’re very serious with that question, and others like it. The Warrens have helped blur the line between fantasy and reality, and now there’s a segment of the population that can’t tell the difference when it comes to horror. Of course I don’t believe in werewolves, for crying out loud. It’s called “horror fiction” for a reason. These things aren’t real, they don’t happen in real life, these creatures don’t exist. But now some people aren’t sure. I immediately lose all respect for any director of horror movies who attaches “Based on a true story” to his work. That tells me they’re aiming their work directly at that confused crowd who can’t tell the difference between reality and fantasy. I avoid those movies because I don’t want to support them with my money.

I’ve been calling the Warrens frauds and con artists for decades, quite publicly, and they’ve never said a word. Don’t you think they would’ve sued me for saying things like that? Unless, of course, they were true. Which they were.

TRISH WILSON: How is the business of writing today different than it was when you first started?

RAY GARTON: Oh, my god, how much time do you have? The business that I entered 35 years ago is gone. Back then, when I had a new book coming out, the publisher would send me a box of author copies. Not anymore. Now if I want copies, I have buy them. If I want a good editor, I have to hire one myself. Promotion is up to the writer. The mid-list is gone, and I was a mid-list writer. I’ve entered a new business and I haven’t figured it out yet.

TRISH WILSON: It seems these days that anyone can call himself or herself a writer, especially through self-publishing. How has Amazon and the Internet changed writing?

RAY GARTON: Ah, I guess I jumped the gun a few questions ago. I touched on that earlier. Yes, these days, in this age of my-opinion-is-better-than-your-facts and I-am-because-I-say-so, anybody can be a writer. Rejection and criticism have been eliminated from the business by Amazon and digital self-publishing. Also the need to have any writing ability whatsoever. That sort of thing is no longer an obstacle.

I was approached by a self-published writer for a blurb. In his request, he added, “I hope you’re not one of those people who’s hung up on things like punctuation and grammar and spelling.” Well, as a matter of fact, I am, which makes me an anachronism, because it turns out those things aren’t important anymore. I like to provide blurbs for other writers when I can, but I only do it if I actually like the work. With some self-published writers, in addition to bad punctuation, spelling, and grammar, I come across things like “at my beckoned call” instead of “at my beck and call,” for example. Those are things a good editor would catch. But nobody seems to mind. Except me. I encountered a self-published writer who, when asked what he liked to read, said, “I don’t have time to read. I just write.” I’m sure that fact is glaringly obvious in his writing, but I didn’t read it to find out.

Don’t get me wrong, there are some talented writers who self-publish. But they don’t make up the majority of what I’ve encountered. Amazon and the internet have devalued writing and literature, like they’ve devalued everything else, and in the process, they’ve made it possible for people with no understanding the English language and no writing ability to call themselves writers. And if you point these things out to them, most will fly into a rage and call you a snob. Their work has never been rejected or edited, and they are convinced that it is absolutely perfect as is, and if you say otherwise, you’re the problem, not the work. And they do publish it as is. It’s a brave new world.

My advice to writers who self-publish is to get a good editor. It’ll cost you, but it’ll be worth it. Unless you’re one of those people who aren’t hung up on things like punctuation and grammar and spelling, of course. But if you aren’t, then calling yourself a writer will never make you one.

TRISH WILSON: Have you ever based your stories on experiences in your own life or people you know or have read about?

RAY GARTON: I think all writers do that, even without realizing it sometimes. I’ve always drawn on my own experiences when I write. There are pieces of my life in every book. Some years ago, a friend pointed out to me that I had been doing that even more than I thought, without knowing it. We all do it.

TRISH WILSON: You've mentioned in previous interviews that you'd like to try your hand at humor. How would you go about that? What other genres would you like to try?

RAY GARTON: I have. My novel Sex and Violence in Hollywood, which I still think is the best thing I’ve ever written, is a humorous thriller. But when you’ve worked under a particular label for a while, it’s difficult to get people’s attention when you do something beyond that label. The label creates expectations. I’m not complaining. I’m a horror writer and I make no apologies for it, I’m proud of it. It’s nice to branch out sometimes, though. It’s just hard to find an audience for it.

TRISH WILSON: If you could have dinner with any of your characters, which one would you choose?

RAY GARTON: Probably Rona Horowitz from Sex and Violence in Hollywood. She’s a brilliant attorney who specializes in high-profile cases and I find her fascinating.

About Ray Garton

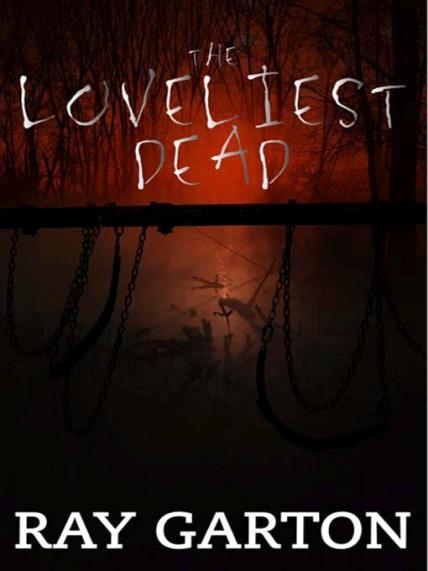

Ray Garton is the author of the classic vampire bestseller Live Girls, as well as Scissors, Sex and Violence in Hollywood, The Loveliest Dead, Ravenous, and dozens of other novels, novellas, tie-ins, and story collections. He has been writing in the horror and suspense genres for more than 30 years and was the recipient of the Grand Master of Horror Award in 2006. He lives in northern California with his wife Dawn where he is at work on a new novel.

About Trish Wilson

Trish Wilson had enjoyed telling scary stories to a captive audience since she was a child. She grew up in Baltimore, the home of Edgar Allan Poe who has inspired her to write. Due to her love for horror and dark fiction she joined Broad Universe, a networking group for women who write speculative fiction. Her short stories have appeared in Zippered Flesh 2, Zippered Flesh 3, Teeming Terrors, Midnight Movie Creature Feature 2, Wicked Tales: The Journal of the New England Horror Writers Vol. 3, Heart of Farkness, and more. She won a Best Short Story mention on The Solstice List@ 2017: The Best Of Horror for Invisible, which appears in Zippered Flesh 3.

In addition to horror, she writes erotica and romance as Elizabeth Black. She lives on the Massachusetts coast in Lovecraft country. The beaches often call to her, but she has yet to run into Cthulhu.