On this month's Special Page:

An interview with the New York Times best-selling author, film director, and musican John Skipp

IN THE "SPECIAL PAGE" ARCHIVES:

Tim Waggoner

JG Faherty

James Longmore

Nancy Kilpatrick

Kathe Koja

John Skipp confabbing with star Kayla Dixon as they set up the next camera setup for the movie "Doppelbanger." See the trailer HERE.

You can listen to Skipp's song "Nothing is Wrong": the link is at the bottom of this interview.

John Skipp is a New York Times bestselling author, editor, film director, zombie godfather, compulsive collaborator, musical pornographer, black-humored optimist and all-around Renaissance mutant. His early novels from the 1980s and 90s pioneered the graphic, subversive, high-energy form known as splatterpunk. His anthology Book of the Dead was the beginning of modern post-Romero zombie literature. His work ranges from hardcore horror to whacked-out Bizarro to scathing social satire, all brought together with his trademark cinematic pace and intimate, unflinching, unmistakable voice. From young agitator to hilarious elder statesman, Skipp remains one of genre fiction's most colorful characters.

John Skipp interview by Trish Wilson

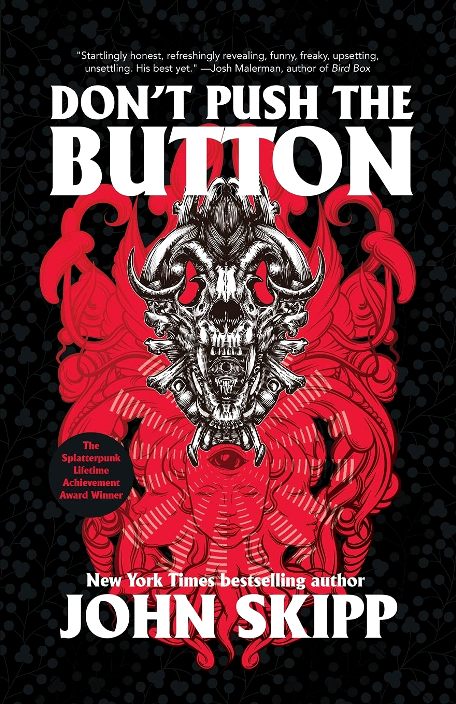

TRISH WILSON: You are announcing your retirement after 40 plus years writing. Tell me about your final project, "Don't Push the Button", and what your future goals are.

JOHN SKIPP: To be clear, I'm not retiring from making weird shit. I'm just retiring from writing and publishing fiction. I've published 25 books as author and/or anthologist, so it's not like I'm ripping you guys off or anything. For anyone who wants to read me, I've left a sizable paper trail. And when I finished compiling Don't Push the Button – which is a collection of like 16 short stories, including two sets of ABCs, which amount to 26 short-shorts apiece, on top of a couple short screenplays, a couple essays, and an introduction to each and every one – I sorta felt like I'd said everything I had to say in book form. And it was time to call it a day.

The good news is, I really love the book. I think it's the most personal thing I've written, and also has the widest range of concerns. About life. Hope. Horror. And what it all means. It feels like I finally wrote my life's mission statement, got it all off my chest. And it was super-gratifying to have Josh Malerman say, in his intro, that he thought it was my best. Cuz that's how you wanna go out.

The other good news is, this frees me up to devote the rest of my life to making movies and music, which is the source of all my joy right now, and pretty much all that I want to do. I figure if I can write and record 50 really good songs between now and the day I die, I will have done pretty well. And I absolutely refuse to die without making at least three feature films I'm proud of.

TRISH WILSON: Did you have mentors early in your career who helped you? If you did, who were they? What kind of help did they give you? I've noticed some writers have had mentors and they've maintained professional relationships and even friendships with them.

JOHN SKIPP: Nope! It's weird but true. I've never had any wise elders advise me, or steer my development, or take an interest in me that I didn't bring to them first. Even as a kid, I made my own creative choices. I taught myself guitar. I taught myself to write and draw. I'd only read two plays when I wrote my first one, and my drama teacher Tim Jecko staged it as one of the two big ninth grade projects at Stratford Junior High in Arlington, VA. (The other was Ionesco's "Rhinoceros".)

So yeah, actually, Mr. Jecko was probably the closest. He was a great guy. He loved the theater. He loved us kids. He was great at collaborating with us, inspiring us to be actively engaged in the arts. But I was already the creative writing editor of the school paper, and writing songs, and singing in a rock band. So I was pretty much a self-starter. I've always tended to lead more than follow.

When I moved to New York City in '81, one of the first things I did was sell a story to T.E.D. Klein at Twilight Zone magazine. He was the guy who helped me most in the early days: buying my fiction, and giving me a letter of recommendation that Craig Spector and I used to sell The Light at the End to Lou Aronica at Bantam Books. But again, he didn't mentor me, take me aside to give me advice. He just really liked my stuff.

What's really weird is that, as I gradually went from young punk to old bastard, I wound up teaching, publishing, encouraging and/or collaborating with a lot of younger writers who kinda saw me as a mentor. In a way, I wound up being the guy who I wished had been there for me when I was a kid. So that turned out kind of nice.

TRISH WILSON: How did you come to write splatterpunk? What drew you to it? What kind of conflict is there between "classic" horror and splatterpunk, or as you referred to it in a 2015 interview with Cemetery Dance, "trashy v. classy conflict"? You addressed this schism in your segment (co-written and directed with Andrew Kasch) "This Means War", for "Tales of Halloween".

JOHN SKIPP: I'm glad you invoked "This Means War" as a splat indicator! Cuz, yeah, it was really as silly as that. When I hit my first horror conventions, I didn't know anyone, and all I'd sold were a handful of Twilight Zone stories. The older guys didn't have a lot of use for me, although Doug Winter was awesome, and Dennis Etchison was kind. And then, when The Light at the End took off, everybody was like, "Who the fuck let THESE guys into the party?" (laughs) And the only guy Craig and I felt a real simpatico with was Dave Schow, who also came up through Twilight Zone with me, and who was blisteringly talented. We were the young upstarts who were punching really hard at the cozy stereotypes of the era, as influenced by ferocious motherfuckers like Harlan Ellison, George Romero, Kurt Vonnegut, John Waters, Hunter S. Thompson, and underground comix like Skull and Slow Death as we were by the venerable classics.

But the thing was, we loved the venerable classics! I grew up on Poe, Bloch, Bradbury, Bierce, Saki, Stoker, Shelley, M.R. James and Shirley Jackson. But I also grew up in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where the traffic cops carried submachine guns, and people died in the streets, so I related a lot more to Lord of the Flies than The Hardy Boys. And speaking personally, I didn't have a lot of respect for academe. I was more from the Frank Zappa school of "Educate yourself, if you have any guts."

Bottom line: there were a bunch of elder statesmen in the field at the time who were more from the professorial leather-patches-on-the-elbows end of the food chain, and they didn't much care for our street-level hardcore literary hijinks. From where I stood, writing horror fiction was a revolutionary act, telling harsh truths in the service of peeling back the bullshit and waking people up to the monstrous injustice of the world. Which is to say, I was probably totally insufferable. (laughs)

That's why I think "This Means War" is funny. These people shouldn't have been fighting each other. They're both coming from a place of love. But people get territorial and touchy, to the point where arguing about nonsense like "loud" and "quiet" horror almost seems to make sense. And the next thing you know, there's blood all OVER the fucking place!

TRISH WILSON: What is your greatest fear?

JOHN SKIPP: Oh, I got a million of 'em. Professionally, my biggest fear has always been taking on shitty projects for the money, and letting them poison my well of creativity, to the point where I hate the very thing I love most, which is pouring my heart into my art.

TRISH WILSON: You wrote the script for the movie "A Nightmare on Elm Street 5: The Dream Child" along with Craig Spector and Leslie Bohem.

JOHN SKIPP: Case in point. Fuck that movie. (laughs)

TRISH WILSON: As I mentioned earlier, you also co-wrote the script for "This Means War" for "Tales of Halloween" with Andrew Kasch. In addition to writing, you directed. How did you come to work on these projects? What was it like working in Hollywood?

JOHN SKIPP: Well, I'm not a big fan of Hollywood, per se. But I looooooove movies. And after the horrible experience of Nightmare 5, I determined I'd rather work in a gas station than be a Hollywood screenwriter. If I was going to do movies, I'd have to become an actual filmmaker.

So I took directing and producing crash courses with Dov Simens at the Hollywood Film Institute, which were incredibly instructive. (Former students include Tarantino and Spike Lee.) Dov breaks it all down to the nuts and bolts: how to budget and schedule, who to hire, for how much, and how to work with each of the departments, from actors to fx to locations to makeup and hair. Cameras. Lenses. Lighting. Transpo. And the ever-present dilemma of raising money. I'd learn more practical info in two days with that guy than you'd learn in four years of film school.

I've often said that the only good thing I got out of Nightmare 5 was meeting Andrew Kasch. He interviewed me for his excellent documentary Never Sleep Again: The Elm St. Legacy, with co-director Daniel Farrands, where I said everything I have to say about that piece-of-shit movie.

And at the wrap party, Andrew told me that he'd been a fan of mine since high school, and that he'd always wanted to work with me. So over the next several years, we made a bunch of short films, often with Cody Goodfellow, culminating in Tales of Halloween and another anthology film called Monsterland, where Andrew and I did the wraparound and included our first film, Stay at Home Dad. Which Cody wrote, produced, and did the music for. A man after my own heart!

TRISH WILSON: You described your new short film Doppelbanger as "half karaoke horror, half extremely dark Bizarro romantic comedy". Where did the idea come from and could you talk more about the movie?

JOHN SKIPP: Oh, I could talk about Doppelbanger all day! I fucking love that movie. (laughs) It started as an idea for a pitch to Creepshow, where my friend Dori Miller and I had just written an episode called "Times is Tough in Musky Holler". It was just a little story about a nice, lonely guy with a terrifying doppelganger, who falls in love with a dangerous woman who just happens to have the world's nicest doppelganger!

But then I realized that there were a lot of ideas in there that I wanted to explore about the nature of romantic love, and of bifurcated souls who are deeply split between their best and worst impulses. It's deep, dark material, but also lovely and funny and sad. And what can I say? It called to me.

I started writing the feature on December 28th, 2019, on a two-week trip back from Portland to Los Angeles. And within the first five pages, I realized that a bunch of the story was set in a karaoke bar. Which meant that I had to write a bunch of songs for the characters and their doppel-selves to sing. Which was, in itself, a very exciting challenge.

So I finished the first draft in the first week of March, 2020, with the hope of shooting it as an ultra-low-budget feature in September. But then the rumors began about this potential pandemic called Covid-something-or-other. And word had it that the world was about to shut down.

I realized that if I was gonna be stuck in my house for a couple of months... (laughs) ...which is all we thought it was going to be, then I'd better get myself a little recording studio, so I could at least vamp out some demos of the songs while I was waiting. I did some research and found that GarageBand might be a great solution for me. All I had to do was buy a MacBook Pro, with the software already installed, and a little midi keyboard, and I'd be good to go.

So I got the keyboard, and priced the Mac at Best Buy. It was just within my range. But then suddenly, a notice flashed across my screen, saying that Governor Kate was shutting down the state of Oregon, effectively immediately.

"FUCK!" I yelled, and jumped in my car, and blasted to the nearest Best Buy in record time, squealing into the parking lot and racing to the front door. Where I was told that I couldn't come in, because we were in quarantine lockdown. To which I screamed "NOOOO!!!"

But then they said that if I knew what I wanted, they could bring it to the door and sell it to me. To which I screamed, "YESSSSSS!!!" Then I went home. Spent the day studying the program. And the next day, I wrote my first three pieces of music.

From there, I went on to write and record 36 pieces of music for the film, all the while refining it on a shot-by-shot, beat-by-beat basis. In the process, I taught myself how to play piano, which is something I had always wanted to do. And in the end, I wound up playing or programming all the instruments, thereby making this an utterly transformational experience.

By then, it was May, and the pandemic was still going on. So I wrote a bunch of the stories that wound up rounding out Don't Push the Button, including "The Inward Eye" (my most autobiographical story), "Little Deuce", "Tendrils for Days", "No Morphic Field Like Home", and "Skipp's Self-Isolating ABCs of the Covid-19 (Phase One)". At that point, I realized I had a book. And when Leza Cantoral and Christoph Paul of Clash Books expressed interest, we had ourselves a deal.

Of course, my Doppelbanger deal fell apart, as well as another bigger film (based on my short novel Conscience) already nipple-deep in development. So I finished the book, and wrote another six hours of music, including 45 minutes of soundtrack for Josh Malerman's online novel Carpenter's Farm, and all the music that wound up on my new albums, The Antidote to Fear and Cry Me a Rainbow.

TRISH WILSON: You described The Antidote To Fear as " a collection of songs documenting the end of the Trump era, the first years of Covid, and his own restless journey." Would you please elaborate?

JOHN SKIPP: Sure! I was responding directly to all the chaos in the air. So "Don't Run When the Devil Comes" relates directly to the street protests around the George Floyd murder. "Ghosts of Dive Bars Past" was my response to all the beloved watering holes going out of business. "Tragic"is a lamentation of friendships lost to Qanon horseshit. "Queen of Justice (And the Broken Whole)" is my tribute to Ruth Bader Ginsberg's passing. And "The Long Way Home" actually features chilling audio taken directly from the January 6th assault on Congress.

TRISH WILSON: I especially liked "The Long Way Home". It's haunting and dark.

JOHN SKIPP: Thanks! And the title track is my message of hope at the end. Because without hope, we're screwed. But once that album was constructed, I still had all these evocative instrumental pieces. And those all went into Cry Me a Rainbow, which really functions like an elaborate movie soundtrack to the last two years.

TRISH WILSON: What genres do you prefer? How do you create your music?

JOHN SKIPP: My favorite genre of music is "good". (laughs) And the fact is, I'm feeling super-wide open to exploring every single style I've ever enjoyed. That's why the pieces range from rootsy rock to prog rock, blues, soul, triphop, reggae, lounge, exotica, experimental, electronic, ambient, and nu wave artpop, all the way to the Neil Young-by-way-of-Frank Zappa country of "Don't Fight the Civil War Again (My Friend)", which Cody Goodfellow performs as "Cowboy Rusty" in the Doppelbanger short.

Speaking of which: Doppelbanger languished for about a year, which did not make me happy. But then my friend and former writing student Brian Asman came by for a beer on my porch. He'd been branching out into various multi-media projects. And he told me that he'd like to invest in a short film of my choosing, with me as writer/director.

Now I gotta tell ya, offers like that don't come up every day. And since Doppelbanger was pretty much my A#1 priority, we decided to do a Doppel-short. And I started digging through the feature script, looking for moments to trash-compact into a solid, short, shootable script.

At which point my fx artist friend Eli Dorsey said, "You got money to shoot? Great! You're gonna put the footage in the actual feature, right?" And I went, hmmm! What if – instead of cannibalizing the feature – I just came up with an original scene I could add to the feature?

That's when my writer/drummer friend Nathan Carson suggested I might wanna meet Kayla Dixon, the lead singer of his doom metal band Witch Mountain. I'd heard her voice, and knew she was phenomenal. But when I found out she could act, had rigorously trained in musical theater, and had appeared in Portlandia and opposite Elijah Wood in I Don't Belong in This World. I reached out to her, and knew at once that she was both of my female leads. My "Belle" and "Doppel-Belle".

This was April of 2021. And from that moment on, I dropped everything else, and devoted myself one trillion percent to the film. Location scouting till we found a fantastic karaoke joint called The Baby Ketten Klub. Found an amazing director of photography named Philip Anderson, who was also an impeccable Steadicam operator. Found a sharp line producer named Vincent Hoai Pham, and together pulled together a fantastic Portland cast and crew, with an emphasis on diversity and serious skill. All our leads are people of color, including Kayla, Ashley Song ("Brandi") and Timothy Krabill ("Randy").

In the process, I conceived of and nailed down the shooting script, my friends Linda Rand and Danger Slater taking dictation while I wildly paced and narrated. Then I wrote, performed and recorded all 16 pieces of music for the short, including Kayla's big blues number, "Be Nice to Me". (Linda, with her great visual eye and intuition, also took a ton of still shots, helped me find the location and nail down nice Belle's Billie Holiday-inspired look with her designer friend Kristen Behlings. Meanwhile, Danger – an amazing writer of Bizarro horror freakiness, who I'd published four books with on my Fungasm Press label – played "Buzz", a wannabe karaoke bar Lothario.)

I spent three months in pre-production, rehearsing the cast and breaking down every single shot with Phil. Then, on August 2nd, we went in with our team and two Red Komodo cameras. And in 12 hours, we shot our entire 15-page script. Which was fucking unheard of. The crew was stunned and ecstatic. They couldn't believe how much work we got done, and how goddam well it played.

Then came the arduous search for an editor. In the past, Andrew Kasch did that job, until he got snagged full-time by DC's Legends of Tomorrow. And my other favorite editor to work with, Charles Pinion, was busy polishing up his jaw-dropping shot-on-video features Red Spirit Lake and We Await for their gorgeous re-release from the distributor Vinegar Syndrome. And I'm a director who needs to be in the room with my editor for every single cut of every single shot, because I'm verrrrrry specific about that shit.

Fortunately, Vincent finally found us a young local editor named Nick Lee, who totally kicks ass. Together, we trimmed it down to its tightest fighting form. And that's the version that's playing the Toronto Short Film Festival this week, at the beginning of our international festival run.

TRISH WILSON: What is it like for you to watch a movie you worked on? Is it as surreal as I suspect it is?

JOHN SKIPP: Well, depends. With Nightmare 5, I just wanted to shoot myself. But with Doppelbanger, or the stuff I did with Andrew, I'm just SOOOOOOOO HAPPY it's ridiculous. There's nothing like pulling a first-rate team together, and meticulously building a dream out of thin air. When it works, it's just the most satisfying feeling in the world. Which is why it hurts so badly when somebody fucks it up.

Now it's all about getting the feature financed and filmed. Come hell or high water, I'm looking to get that done before the year is out. Only then can I move on to the next movies on my list.

TRISH WILSON: You wrote the novelization of the horror film "Fright Night" (1985). How did that project come your way? How different is it writing a tie-in book like "Fright Night" as opposed to other novels?

JOHN SKIPP: They gave Spector and I a nice chunk of change, and we had a month to write it before the movie came out. It was a fun challenge, to take somebody else's story and make it come alive on the page without changing any of its essential plot points. It was also Craig's first time actually typing on a typewriter. (We'd just finished The Light at the End, which I wrote while we plotted from his original idea. Next up was The Cleanup. We didn't get computers until our third real novel, The Scream.)

TRISH WILSON: How is writing a script different from writing a novel? Do you have a preference?

JOHN SKIPP: Well, books are much harder, and take a lot longer, because you have to explain everything. The words are the only tool at your disposal. But with scripts, you're just giving instructions for the director, the producers, the actors, the set designers, camera crews, and everybody else involved. Then it's their job to make it come true.

At this point in my life, I have zero interest in writing novels, and almost no interest in reading them. They just take too goddam long.

TRISH WILSON: You've often said short stories and novellas are perfect for the horror format, especially for TV and movies. Why is that?

JOHN SKIPP: Because you don't have to throw away three-quarters of a big fat bloated novel, that's why! (laughs) The stories are already neat and concise. Visual mediums are streamlined intrinsically, so that makes them a natural fit. And nothing kills suspense or momentum like 100 pages of padding, which is what I think most contemporary novels suffer from.

TRISH WILSON: You've written alone and with collaborators such as Cody Goodfellow. How has that working relationship come to be? What do you like about collaborating with another author? What are some disadvantages of collaborating?

JOHN SKIPP: Be it Cody, Kasch, Spector, Autumn Christian, Laura Lee Bahr, Marc Levinthal, Shane McKenzie, Dori Miller, or any or every performer or crew person I've ever had on my team: with the right person or people, there's noooooothing I love more than collaborating. I learned that from jamming with bands, and those long-ago stage productions with Mr. Jecko. It's just so much fun to bounce ideas back and forth, play with someone who sees the angles you miss. It expands the work. It expands the process. It expands my joie de vivre.

And, of course, film is the ultimate collaborative medium. Not just because of all the people required, but because the form is an intrinsic collaboration between story, sound, and vision. All of these elements interplay. That's why there's nothing I'd rather do.

TRISH WILSON: What do you think makes a great horror anthology, either in cinema or in print?

JOHN SKIPP: The same thing that makes anything great, right? Selecting the right ingredients. You have to trust the tastes of the editor or producer curating the event, like you trust the chef who's curating your banquet. A variety of flavors that compliment each other, creating a gestalt effect that's greater than the sum of its parts. A delicious medley of colors, textures, and tones, with kaleidoscopic range. Extra bonus points for playfulness, so long as you can bring the meat cleaver down as needed. And no dreary one-note repetition, cuz nothing kills an anthology's buzz like beating its theme to death.

TRISH WILSON: Which writers have influenced you? Who are some of your favorite writers?

JOHN SKIPP: Well, depends on which kinds of writers you mean. Aside from everyone mentioned above, if you're just talking fiction, it's easy to see, just from looking at all the people I've published in my anthos or on Fungasm Press. But then you've got screenwriters, and the hundreds I worship. And don't even get me started on songwriters!

In my last short story collection, The Art of Horrible People, I had an index at the back featuring 1,200 of my favorite artists in every field. For an honest and comprehensive answer to your question, I think you'd need to check that out. Otherwise, I'm just skimming in shorthand.

TRISH WILSON: Please include your web site, social media links, and your Amazon Author Page link. If there is anything else you'd like to add, feel free to do so.

JOHN SKIPP: I don't have a proper website up right now, but I'm workin' on it! In the meantime, you can find me at Facebook here.

https://www.facebook.com/john.skipp.7

I'm also technically on Twitter and Instagram, but honestly? I'm never there.

You can get Don't Push the Button at Amazon or most regular retailers. But your best bet is to get a signed copy direct from Clash Books, at the following link:

https://www.clashbooks.com/new-products-2/l9zyvzw5pcgtd221ig4b8il1mjkj4f

Same for the albums, which are available on Spotify, Amazon, Apple+, YouTube, TikTok, Pandora, and a trillion other places. But I'd be happiest if you got it direct from me:

THE ANTIDOTE TO FEAR

https://johnskipp.bandcamp.com/album/the-antidote-to-fear

CRY ME A RAINBOW

https://johnskipp.bandcamp.com/album/cry-me-a-rainbow

Doppelbanger isn't available online right now, because it's playing the festival circuit. But you can see the trailer here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KrHCN0g58oY

And here's a nice music video for the song "Nothing is Wrong" which appears both on The Antidote to Fear and in Doppelbanger:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VsI4h_lDwww