FICTION BY GARRETT ROWLAN

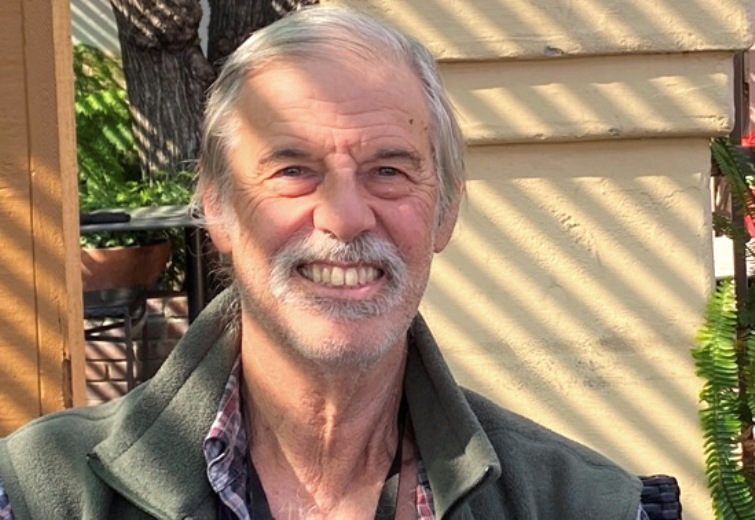

Garrett Rowlan is a retired teacher who lives in Los Angeles with two cats. He has work forthcoming in two anthologies and a magazine.

His website is garrettrowlan@com.

THE IMPOSSIBLE NARRATOR

by Garrett Rowlan

Inside a wall-mounted box behind a panel of thin glass two people hold poses. The girl is me, Valerie Booth, years before I died of cancer. The man is Harold Lucas. We are both alive inside the frame, between existences, between dimensions: inside looking out.

I made this box a couple of years before I died. Now I’m trapped inside it with Harold. This kind of half death feels like my one marriage, back in the 1960’s, before I accepted I was gay. Now as then, I want out. Who can help me?

Harold and I woke three weeks ago to find ourselves inside the wooden box, his head on my lap. Everything surrounding us was the same as it was fifty years back when we were photographed in a wooded clearing without our knowledge or consent.

The photograph, I soon remembered, was snapped surreptitiously by a young man named Tom Shelton in the Northern California town of Zephyr, near Santa Rosa.

Knowing I was dead, I scrambled away from Harold and saw myself—naked, lithe, and seventeen—reflected in the thin glass front of the wooden box that sealed us off. I was a teenager again! But I knew right away it was wrong. I should be ashes in an urn.

*****

Sounds reach me through the glass. The doorbell rings. Mrs. Rita Gunn, the owner of the shadow box we’re inside, walks down the stairs and we assume the position we are hardwired to take for viewers. She passes us wearing jeans and a denim blouse and answers the door. I hear the shuffle of footsteps and the murmur of conversation. I count different voices, a group gathered. This is some UCLA Extension School group, come to tour a couple of private homes that have artwork. They talk, admire, nod, and eventually they come our way.

We hold the pose. I’ve even tried to move a finger on these occasions and I can’t. It’s something metaphysical, a mandate not to stir the surface of reality. People walk to the front of the box and look in. I feel their eyes.

“My ex-husband bought that,” Mrs. Gunn says. “The artist’s name was Valerie Booth.”

Harold hears my name and grumbles. There was always this possibility, and now he knows I made the space we’re in.

“It’s a moment captured,” the art teacher says. “The box is meant to convey a story; a mystery with the lovers at its center.”

One old man lingers. He looked faintly familiar, and only leaves when the art teacher calls his name.

“Mr. Shelton,” she says. Shelton? Could he be an old man version of Tom Shelton, fiftyor so years on?

The old man moved on. We don’t see people looking in as much as we feel them, the freeze from eyes.

When they leave, we can move around. Harold springs to his feet. “You made this box?” he asks, his hands on his hips. I wonder if he had that expression just before his fatal heart attack.

I make a one-shoulder shrug. “I did, but I made art, not a jail. I don’t know why we’re here.”

His expression goes through several responses, ends with a sigh. “Is there anything else you want to tell me?”

“Yes, I think the person who took the photo of us was just here.”

*****

I took art appreciation to meet women. I didn’t mean dead ones. Yet as soon as I saw the shadow box I knew I was seeing the best photograph I ever took, and after I heard the name “Valerie Booth,” I went outside in a daze.

“Oh yes, Mr. Sheldon,” Professor Smith says to me. “Ms. Booth taught at UCLA for a long time. She died a couple of years ago.”

It’s a bright, windy Saturday afternoon. The skyline is sharp over this winding, narrow street in South Pasadena. Professor Smith gathers us together. She is a slender woman with tattoos, caterpillar eyebrows, and black hair spiked into stubby tendrils like a sea anemone. Despite her rebel attire, she has an eager-to-impress manner. She addresses our small group.

“By the way, Mrs. Gunn wants to say that certain of the pieces that you have seen are for sale by arrangement.” She works those eyebrows, dishing the dirt. “She is going through a divorce. I have her information if you’re interested.”

Professor Smith then tells us that we’re going to go to another private viewing, this in a house in San Marino. I slip out of the group without anyone noticing. I stay behind and remember.

Valerie was my first girlfriend. Our first kiss came in the small photography lab at Zephyr High School, the tiny dark room with its coves of light and the smell of developing fluids. We went together for a few months, kissing and groping in the front seat of my father’s beat-up truck, but going no further.

One afternoon, after she stopped taking my phone calls, I was riding my bike on the road that led south to Santa Rosa. I saw a Ford Galaxie nearing. Obscured by bushes, I saw Valerie in the front seat. Harold Lucas, driving, was the son of a vineyard owner.

In my bike, I emerged from cover and pedaled furiously after them.

And then I took the photograph that is my shame.

*****

Harold acts with a new respect, or perhaps trepidation. In a sense I’m his creator. I summoned him back from the dead, this space we share. Its trees soon become walls, after two dozen steps back. “So you made this?”

“Cut and joined the wood myself,” I say. I give an account of our enclosure that holds his interest until his expression grows stern.

“Did you know he’d taken this photo?”

“No,” I say. “Not at the time. He told me he saw us driving by, and followed.”

“And when did Tom tell you this?”

“A few years later, down in Los Angeles. He bribed me into having sex in return for the negatives. You see,” I add, and it feels good, “you weren’t the only one who took advantage of me.”

He lets that pass. “When was this?”

“I was in college. He wanted what he didn’t get when we were teenagers.” Now I look away to the staircase whose upper landing I can’t see, as if it rises to eternity. “I slept with him. That’s how I got the negatives.”

It was my night of shame, as I have thought of it. It started with getting out of Zephyr and going down to Los Angeles for junior college beginning in September, 1980. When I transferred to UCLA in 1982, I switched my major from Literature to Art. As the decade progressed, I accepted that I was a lesbian.

I was making it (oils, collages) when I got the call from Tom Shelton. I had forgotten about him and scoffed at his revelations, but felt my gut drop when a couple of the pictures were sent to me care of the school. It really wasn’t a negotiation by then; I had a budding reputation to protect. I did what I had to do, and in the morning he gave me a key and told me a post office box number.

“So you had sex to keep your job?”

I nodded. I stayed at UCLA twenty-four years. I never heard from Tom again.

After forty years in southern California, I had enough. I retired and Karen (my significant other) and I moved to Santa Rosa. I unpacked boxes closed for decades. I found the negatives that Tom Shelton had extorted from me.

Though Harold is young-looking in our cage, his eyes are those of an old man who divorced three times and whose children ignore him. “Why did you make this box after all those years? What good came out of that time?”

“I had to deal with it,” I say.

“By showing it to the world?”

At the time I made the box, I was an old woman, already touched by mortality and a doctor’s diagnosis. “I couldn’t let it go, I just couldn’t. When I saw the picture…when I held it in my hands after having not seen it for so many years, I saw how beautiful I was!”

I couldn’t resist. I was young, pretty, and the center of attention, as if not only Harold but from the waiting world that would look at me. In the shaft of sunlight, my back was slightly arched like a bow about to be strung.

Did I suspect that I was being watched in some way…and I was posing, somehow? Seeing that photograph when I was old, I coveted myself. I took pride in my youthful body, and used exhibitionism as art.

*****

I stay when everyone left. I wait. The woman whose house we had visited comes out and stands on the elevated porch. I walk to her. “Hello,” I call up to her, “My name is Tom Sheldon. I’m interested in one from your collection.”

“And why the shadow box?” Rita Gunn asks.

When I was young, I took the camera everywhere. That’s how my story starts. I tell her how I saw Harold and Valerie and how I followed them, furiously pedaling. Traffic was slow, someone had stalled up ahead, and I saw them turn. A quarter mile up the road, I found a locked gate. I ditched the bike and climbed the gate. The camera dangled from my neck. They never saw me or heard the camera click.

Rita Gunn looks at the shadow box. She takes it down from the wall. “Sometimes I look at this and I wonder if she’s saying something.”

“What?”

Rita looks away from the photo to gaze directly at me. “Someone took this photo without consent. That’s what I feel the woman in it is trying to tell me.”

“Who knows, after all this time?” I tell her.

“I think someone does know. And if that someone ever sees this photo now, he would hear the same thing I hear Valerie Booth trying to say. That she wants to be free.” Rita gives me a searching look, and it’s like turning a flashlight onto my mind, my memory. I see what I hadn’t wanted to see for years, my own cruelty—my own jealousy, too. I was nothing more than a camera salesman and Valerie was a rising academic.

Rita Gunn says thoughtfully, “Maybe only the photographer can change things. You know, find freedom.”

“I think Valerie and I both want that. To make us both free,” I add, “of the past.”

We talk about price.

*****

Days later (though time is an elastic quality in my world) we move for the second time. First, from the gallery to Rita’s. Now we’re boxed and carried to a car. I feel the acceleration and braking and centrifugal force with each turn. “What’s going on?” Harold asks.

“I think we’ve been sold.”

“I don’t like this,” Harold says. “I don’t like this at all.”

In twenty minutes we park, and we are carried into a house. It must be Tom’s. We are mounted on the wall, and the view is across the room is certainly more spacious than we had before.

It doesn’t last. For two days, Tom looks at us in a knowing way, and finally he enters the room carrying a toolbox. He sets us down and examines us through a magnifying glass. We are tilted toward the ceiling. Tom’s shadow falls over us, and in his hand I see a screwdriver. I feel its tip probe the box.

I realize, then, that I have been telling my story to him. He must be the one to free us.

He works slowly, almost reverently. He takes a Phillips head that he uses to loosen the screws from the slots I’d carefully drilled. Twist by twist, we are dissembled, the screws groan like the universe crumpling. The glass in front of us falls away and we are truly naked, with light pouring in from all sides.

We are lifted and set down. I twist my body and look up. I see Tom’s expression as he carries us to the fireplace. He is smiling kindly. He wants what I want: freedom from the past.

We are set down among twigs, scraps of paper, and other kindling. Tom lights a match. The light flares over his face. He sets the match to the pile. I wait for flames to purify, burn away sin. They work towards us.

Harold trembles under my arm. It’s the same pose as before, but now its meaning is different.

“It’s okay,” I say. “It’ll soon be over.”

I pat his shoulder. In this moment, he’s the child I never had, taking comfort in my touch as our world ends. We’re heading for some place we need to be. I don’t know where that is, but this is part of the process.

The sun blackens, and the sky turns to flames that roar down the tree towards us. The background turns to liquid fire. The flames take us and I hear a scream. It might be mine. I dissolve up the chimney and into the sky that is blue, endless, and will not remember.

*****

I sweep the ashes into a floor chute and slap the dust from my hands. It was a good day when I photographed them and a good day when I burned them.

I think about Rita Gunn, divorced and vulnerable, and I wonder, would flesh burn as easily as paper?

I noticed a road running above her home. I could park and creep down without her seeing me and my camera. I could take photographs of her.

I think about how she would burn, if I take it to the next step, the real thing. It’s something to think about.

Definitely.