On this month's Special Page:

Best-selling author Craig DiLouie investigates how the Slasher Genre got its start

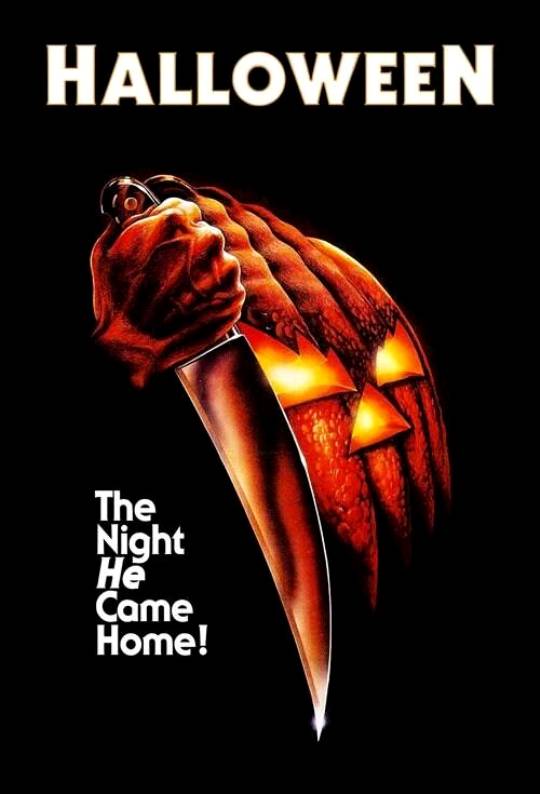

Halloween, the one that most people agree started them all (although others insist it was Psycho)

IN THE "SPECIAL PAGE" ARCHIVES:

Billy Martin (aka Poppy Z. Brite)

Daniel Knauf

Tane McClure

Nicholas Tana

Elizabeth Massie

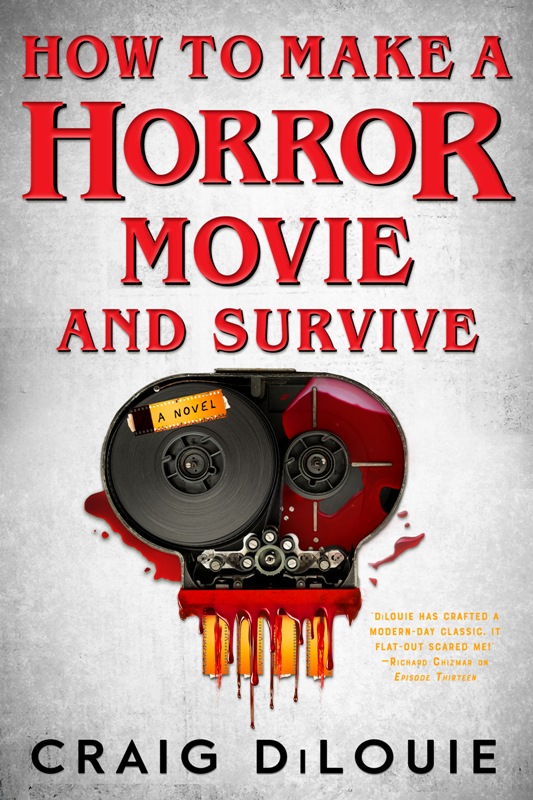

Craig DiLouie is the author of How to Make a Horror Movie and Survive, which will be released by Hachette Book Group on June 18, 2024. Other notable works include Episode Thirteen, The Children of Red Peak, One of Us, and Suffer the Children. Learn more about Craig’s work at CraigDiLouie.com.

Horror: The Never-Ending Story of Survival

(A love letter to the Slasher Genre)

by Craig DiLouie

For me, one of the joys of writing fiction is how much I learn. I’ve explored the psychology of people who join cults, the complete lore of the Antichrist, and how much blood an average human body holds. I enjoyed a deep dive into two fascinating subjects: how movies get made and the films of the iconic slasher era—not only learning a lot about movies but also reflecting on my own role as a horror creator.

Who first conceived the slasher concept is debatable. One might trace it to crime writer Mary Roberts Rinehart, whose novel The Circular Staircase—adapted into the silent film The Bat (1926)—features guests in a remote house hunted by a killer wearing a grotesque mask. Another could point toAlfred Hitchcock’s Psycho with its surprising shower murder, a 45-second scene that took a week to shoot, involving a whopping 75 camera setups.

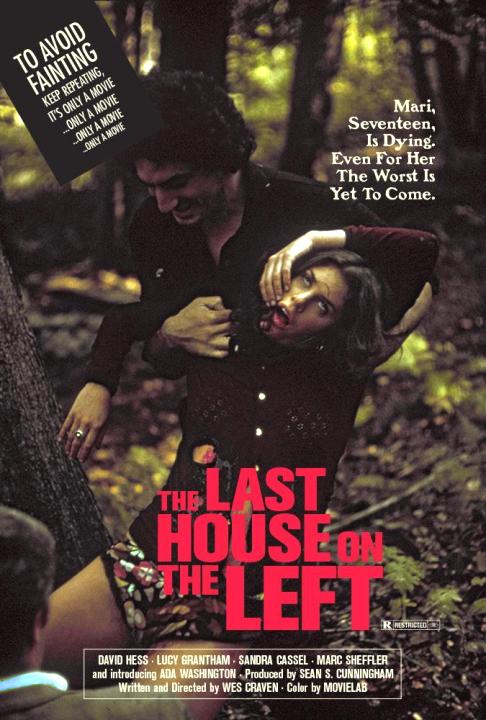

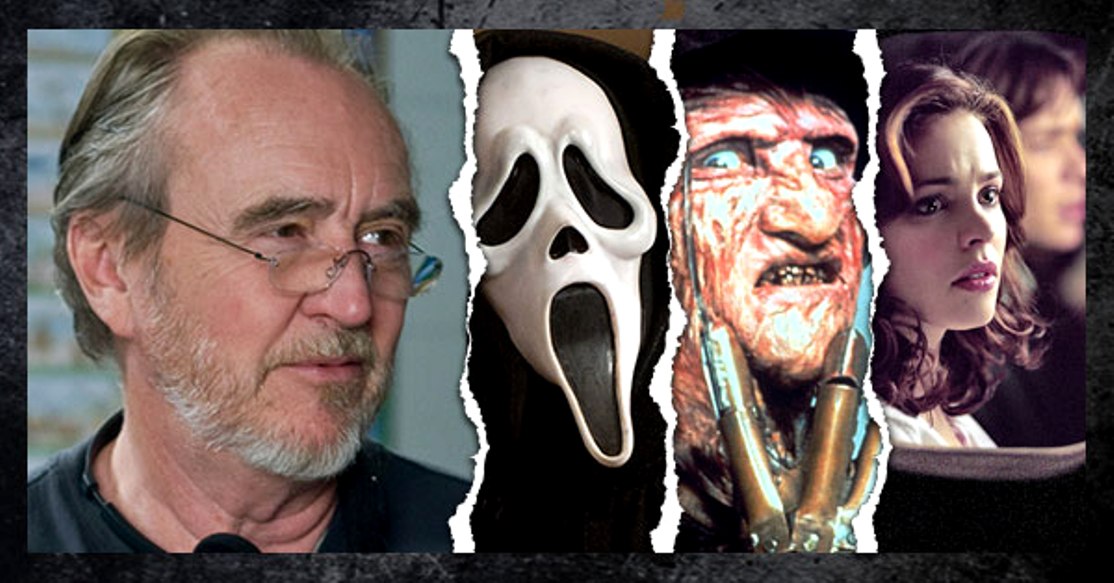

Others could argue for Herschell Gordon Lewis’s shlocky Blood Feast, with its over-the-top carnage that tested the censorial Hays Code. Wes Craven’s gritty and brutal The Last House on the Left. Tobe Hooper’s nightmarish and depraved The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Bob Clark’s Black Christmas, or the creepy Giallo movement in Italy helmed by the likes of Mario Bava and Dario Argento.

Still others might trace the slasher movement all the way back to the Grand Guignol. From 1897, this Paris theater specialized in sensationalistic short plays that served uplive, realistic murder, torture, sex, and cannibalism.And others even further back to William Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus.

Regardless of who first conceived it, the slasher’s roots run surprisingly deep.

My investigations into the slasher era confirmed something I’d suspected about storytelling in general. That it’s not possible—and might not be desirable even if it were—to be 100% original. That every story owes at least some debt to its predecessors, with all stories connected in a chain of story and storytellers, forming an evolving series of archetypal tales going far back in time.

Similarly, Halloween, John Carpenter’s 1978 classic, brought together the best elements of earlier influences—a masked madman on the loose, graphic violence, point of view shooting, jump scares—at the right place and time.With a budget of $300,000, the film went on to gross $70 million in global theater ticket sales—what Hollywood calls lightning in a bottle. If not the fuel, this seminal film certainly proved the spark that launched the modern slasher era.

In Hollywood, the 1970s was a time of auteur directors and bold, experimental films. The 1980s saw the industry ruled by the big studios. Focused on return on investment, they wanted blockbusters that filled seats and turned a massive profit. That meant major stars, dumbed-down formulaic scripts, endless sequels, jaw-dropping explosions and special effects, teen sex comedies, and muscly action heroes. Not necessarily in the horror genre, however, which nonetheless went on to enjoy mainstream popularity.

Carpenter showed you didn’t need massive budgets and Hollywood stars to make a successful horror movie. You only need to deliver horror.

Which was fitting—film or fiction, horror has always been subversive. The black sheep. It’s the Midnight Movie, the drive-in double feature, the titillating exploitation film, the video nasty. It’s a middle finger delivered with an evil grin to society’s comforting fictions, a fractured mirror held up to the human condition. It’s grinning monsters, moldering corpses, strange bumps in the night, broken rules and forbidden knowledge, steamy sex in the backseat under a murderous gaze, an eerie children’s choir setting the mood to venture into a derelict mansion on a dare. Even horror itself is both a genre and not a genre, as horror is really not a story type but an emotion delivered by story.

Horror is, and has always been, punk rock.

The slasher subgenre, and horror itself, exploded in the 1980s as Halloween inspired hundreds of films that received eager funding. By 1984, when the genre arguably peaked, Michael Myers, Freddy Kruger, and Jason Voorhees had become cultural icons.

The most successful movies canonized the genre around what is now a classic formula, the familiar typically delivered with some new element or twist to make it stand out. A monstrous killer massacres a group of obnoxious teens one by one, often on a significant anniversary such as a holiday. The teens are stereotypes who commit the sin of living too large and flouting the rules and are therefore judged. The adults are generally disbelieving, incompetent, or offer a menacing but ineffectual warning. And the final girl, the last survivor, gets knocked on her ass over and over but always comes back swinging, making her the embodiment of both living terror and courage in the face of evil.

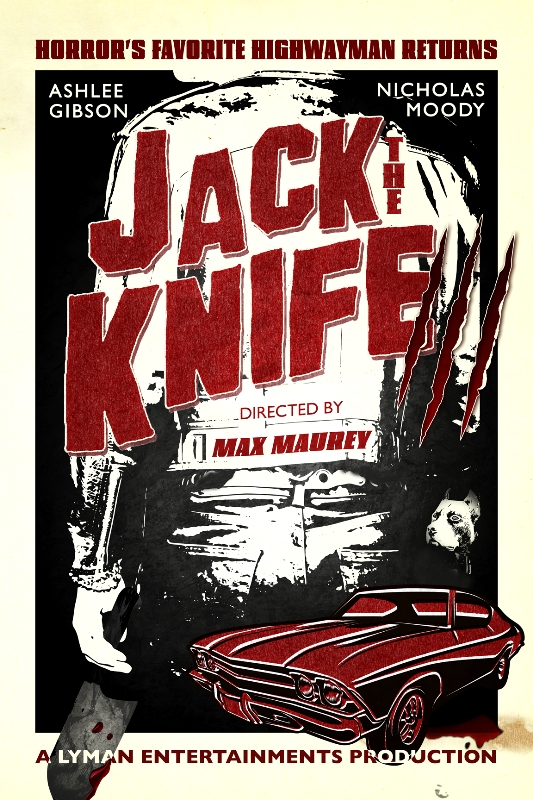

The golden age of the slasher was a time of analog filmmaking, clapboards and hot lights, bulky cameras and film reels, all of it so wonderfully gritty and tactile. Right at the crux of the slasher trend playing itself out and transitioning from classical to campy and self-referential, a transition that director Max Maurey, our protagonist who created the successful Jack the Knife trilogy, feels a dark urge to violently resist.

Max hears the question of whether a horror creator can go too far, and his answer is a bloody no. He doesn’t want to satisfy his audience. He wants to horrify them with one special movie they’ll never forget.

“The first monster an audience has to be scared of is the filmmaker.” Wes Craven said that, and it’s perfect, practically a motto. Not just for movie directors but for all horror creators.

In the slasher’s case, the monster is the surrogate for the director, the final girl the surrogate for the audience. Together, they tell an ancient story of life and death.

On the silver screen, the players frolic, unaware they are all doomed to die horribly. An ancient script rendered in history’s most wonderful optical illusion, the product of persistence of vision when viewing a series of images flashing by at a high rate. The magic of cinema, from the Zoetrope and cartoon flipbooks on to Edison and Dickson and all the way to the slasher flick, all serve one pupose: to scare the audience with gory detail.

The screen is the campfire, the movie a testimony about how to survive, and the surrounding darkness is filled with predators that still live in the genes. The audience comes for horror, a psychological room where they can share and face their collective fears, traumas, and taboos—both the rational and mundane kinds inflicted by the current zeitgeist and the illogical kind lurking deep in the soul. They stay for the catharsis, as one of the players proves worthy to survive, and ritually survive themselves, proving any fight you walk away from is a win.

And feeding these fears, the horror creators, inch by bloody inch, carve out new spaces promising fresh scares and thrills. There are always new monsters to fight in an ancient genre.

Yet today, horror is more interesting now than it’s ever been. We are fortunate to live in a media age abounding in amazing and thoughtful horror stories. Like the slasher villains themselves, the slasher genre always rises again to menace and is today enjoying something of a renaissance.

As fear is such an old and base human emotion, it’s no wonder that horror has endured as both an element of fiction and a genre itself, from the campfire to books and plays to the modern screen. Good horror thrills us, breaks boundaries, makes us confront our fears, asks disturbing questions, induces wonder, and makes us check under the bed, you know, just in case.

Again, it is a very old story.

The funny thing is that outside of art, horror is an emotion that most of us do our utmost to avoid. Why do we eagerly seek it out on the page and screen? And while we can all recognize horror as a feeling, why is it so hard to define as a genre? What makes good horror? When horrifying an audience, how far is too far?

It was these eternal questions that in large part inspired How to Make a Horror a Movie and Survive—a love letter to the horror genre in general and horror filmmaking in particular, shown through the lens of one of the great periods in horror film history: the slasher era.

I hope you’ll check out the novel if you’re interested in seeing how it was done—and what might have been.