FICTION BY RICHARD CHIZMAR

Richard Chizmar is a New York Times, USA Today, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Amazon, and Publishers Weekly bestselling author.

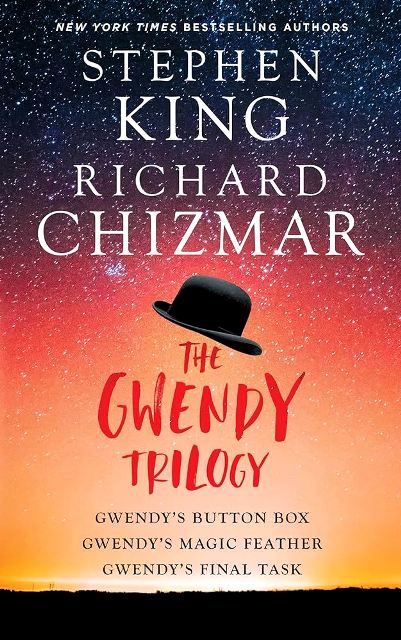

He is the co-author (with Stephen King) of the bestselling novella, Gwendy’s Button Box. He has edited more than 35 anthologies and his short fiction has appeared in dozens of publications, including multiple editions of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine and The Year’s 25 Finest Crime and Mystery Stories. He has won two World Fantasy awards, four International Horror Guild awards, and the HWA's Board of Trustee's award.

Chizmar (in collaboration with Johnathon Schaech) has also written screenplays and teleplays for United Artists, Sony Screen Gems, Lions Gate, Showtime, NBC, and many other companies. He has adapted the works of many bestselling authors including Stephen King, Peter Straub, and Bentley Little.

He is the creator/writer of Stephen King Revisited, and his thirdshort story collection, A Long December, was publishedin 2016 by Subterranean Press. With Brian Freeman, Chizmar is co-editor of the acclaimed Dark Screams horror anthology series published by Random House imprint, Hydra.

Richard Chizmar is the founder and publisher/editor of Cemetery Dance Magazine and the Cemetery Dance Publications book imprint.

LAST WORDS

by Richard Chizmar

I was alone with him when it happened. Sitting by the window in a shaft of lazy September sunlight reading a paperback. It was after lunch, and the day nurse had just gone downstairs with a plate of fruit and a cup of pudding, both of which were barely touched. He had been dozing most of the morning thanks to his pain meds and hadn't bothered to wake up enough to eat much. He wasn't eating much these days even when he was awake.

I marked my page and watched two boys walking on the sidewalk outside, fishing poles perched on their shoulders like rifles, when I heard him whisper something.

I turned to him. "What did you say, Pops?"

His eyes were slits. He could have still been sleeping, but his lips were moving. I got up and walked closer. "You need something?"

A barely perceptible shake of his bald head and then his eyes opened. Cloudy and dull. A snapshot of memory flashed in my mind: this same man leading a conga line at my wedding reception, shirt untucked, tie loosened, those same blue eyes twinkling with mischief and scotch.

"Treasure…hunt," he whispered.

I smiled through sudden tears. "I remember, Pops. Of course, I do."

Another shake of his head.A little harder this time.

"Find the map." He started coughing, his entire body shaking with the effort.

"Here…drink this." I lifted the cup to his lips.

He took a noisy sip of water and closed his eyes. After a long moment, I thought he was asleep again and started to move away when he whispered, "Find the map. Before they do."

I stood there and watched his chest rise and fall, rise and fall.

Fifteen minutes later, he was gone.

*****

My mother and father died in a car accident on I-95 the weekend before my seventh birthday. They were on their way home from buying my presents at the mall, and the guilt I felt because of that at age seven is something I have never entirely outgrown.

My grandfather, widowed himself only two years earlier, raised me and my brother. Like many veterans, he was a complicated and proud man. Prone to long stretches of silent thoughtfulness and restlessness, he was also a wonderful storyteller and a man with an amazing and generous heart.

It was my grandfather who gifted me my love of books and the outdoors and classic movies. He was the one who taught me how to fish and swim and throw a curveball. Everything was a lesson to be learned to Pop, but he made it interesting and fun. He was the best teacher I ever had.

I remember one night after a drenching rainstorm, he handed me a flashlight and led me outside to catch nightcrawlers in the back yard. We filled a coffee can and you would have thought he had revealed the secrets of real magic to me that night.

In a way, he did.

*****

And then there were the treasure hunts...

They were my absolute favorite when I was a boy.

My brother, Lee, and I would wake up to find a hand-drawn map on the nightstand between our beds. We would hurry up and get dressed, rush through breakfast and our morning chores, and slam out the screen door into a brilliantly blue summer day to follow the map's instructions.

The first time we found the map Pops denied involvement and swore that someone else must have snuck into our bedroom under the cover of darkness and left it. Pirates, maybe.

By the time I was ten and Lee was nine, we knew better. But it didn't matter. All that mattered was the hunt.

The treasure maps would lead us across golden fields and grassy hills, into deep dark woods and along shade-cooled creeks where trout and frogs would chase bugs. We would cross those creeks on moss-covered rocks and follow crumbling stone fences until we eventually spotted the towering oaks or weeping willows or fern-choked gullies that marked our destination.

Soaked with sweat and bursting with excitement, we would set to digging and when our shovels clanged on metal, we would drop to our knees and finish with our hands, racing to unearth our treasure.

Our "treasure" usually ranged from new John D. MacDonald paperbacks to carefully wrapped bags of candy to piles of nickels and dimes and pennies. But sometimes more exotic treasures awaited us: a pair of pocketknives, foreign coins from Pops' Army days, one time even a genuine Japanese bayonet from the war.

Eventually, as we got older, Lee grew bored with the treasure hunts and disappointed with our findings, and he stopped going. Not me. I never cared what I found buried in the ground. For me, it was the thrill of the hunt.

It wasn't until I was almost a man that I understood what Pops was doing with these hunts of his. What a gift they were to us. What he was teaching us…

*****

When I called Lee and a handful of other living relatives -- a couple of cousins and one sister too far gone senile to remember she actually had a brother -- to tell them that Pops had passed away, the conversations were short and devoid of many details. Pops had been sick for awhile, so it wasn't unexpected news.

Only Lee asked if Pops had said anything on the day he died.

The question surprised me, and for some reason, I changed the subject when he asked.

I didn't want to lie to him...but I also didn't want to tell him.

Pops’ last words belonged to me.

*****

We buried Pops on a cloudy autumn Thursday.

Lee and his wife, Annie, and their two girls flew down from New York for the service. I offered they could stay at the house with me, but they opted for the local Holiday Inn, as they had the handful of other times they had visited.

With the exception of old Mrs. Potts, Pops' next door neighbor, the rest of the funeral attendees were made up of mostly strangers. What remained of Pops' friends from church and the VA hospital and the VFW. They all shook my hand and clapped me on the back and said nice things in tired, whispery voices.

I held it together until the honor guard fired their rifles and folded the American flag that draped Pops' casket and the bugler played Taps. I accepted the flag from a soldier not much younger than myself with tears streaming down my cheeks.

It was a nice service, and I was grateful to everyone who attended.

On the drive back to the house from the cemetery, I could almost hear Pops' voice from the seat beside me: beautiful day like this is meant for fishing and not much else.

Lee and I said our goodbyes later that night in the Holiday Inn bar, neither of us talking very much about Pops or the past, choosing instead to discuss the upcoming baseball playoffs and his little girls and how his photography business was really taking off. He asked me what the book I was writing was about, but as usual I didn't sense real interest, merely a polite gesture meant to extend the conversation.

We had been best friends growing up, all thru our school years and into college, even though we attended universities more than five hundred miles away. But sometime after Lee got married and moved to New York, we started to drift apart the way best friends and even brothers sometimes do.

I had married -- and then divorced -- my college sweetheart. Wrote and sold my first novel. Quit my job at the newspaper and became a full-time writer. Shortly after, I moved back to the old neighborhood, just a couple of blocks away from Pops and the house we grew up in.

The move made sense to me. I could write from anywhere. And I missed Pops. He was my family and this was my home.

*****

I couldn't sleep. That's why I ended up at Pops' house at midnight, banging around in the dark, looking for the damn map.

I'd lain in bed, running Lee's visit through my head, searching for meaning in the things he had said and the things he hadn't said. Was he still disappointed in me for returning to our little town and writing the kind of books I wrote? Did he think I had settled for this life?

And the loudest voice inside my head: when did I start caring so much about what my little brother thought?

Somewhere between thinking about what Lee had said at the funeral about Pops' will and what he'd said at the hotel bar about buying a new Cadillac, I remembered Pops' last words: "Find the map. Before they do."

Fifteen minutes later, I was slipping my key into Pops' front door and slipping inside like a thief in the night.

*****

I left the lights off. I told myself I didn't want old Mrs. Potts to see a light on in the house and come over to investigate. But I think it was more than that. I don't think I was ready to see the silent remnants of Pops' life. His battered old reading chair.His collection of autographed baseballs on the bookshelf. The family photos on the wall. His faded war memorabilia.

Besides, if there was a map to be found, I knew where I would find it.

I crept up the stairs and down the hallway to my old bedroom and pushed open the door. A sliver of moonlight peeked in through the window. The pair of single beds remained, as did the faded and chipped nightstand that sat between them. A lamp sat on the nightstand. And nothing else: no map.

I opened the single drawer. Empty.

Disappointed, I started to turn and leave when one final thought occurred to me. I picked up the lamp and looked underneath...

...and there it was.

I picked up the piece of paper and unfolded it -- and discovered that it was actually two sheets of paper.

I walked over to the window and took a closer look.

The first sheet was a map. Even in faint moonbeam, I could see that it was drawn in the same detailed fashion as the maps of my childhood. A wave of bittersweet nostalgia racked my heart.

I unfolded the second sheet of paper and found a list of names.

Nine names.

*****

I sat in my truck in the driveway and Googled the names on my phone.

They were all young women between the ages of 22 and 30.

And they had one other thing in common: they were all missing.

*****

I parked my truck in Pops' driveway at daybreak and climbed out with the map and a shovel. Pops had taught me how to dress for the land back when I was a kid, so despite an unseasonably warm September morning, I was wearing jeans and hiking boots, a flannel shirt and a baseball hat. I locked the truck and set off.

For the next ninety minutes it was like walking through a time machine and traveling two decades back in time to my childhood. I walked the same fields and paths and creek beds as I had as a fifteen-year-old dreamer.

Of course, nature had had its way with the land, yet somehow it was just how I remembered it. A sense of peace and calm settled over me as I walked deeper and deeper into the wilderness. All the years I had lived here after moving back and it had taken one of Pops' treasure maps to get me out here again. Maybe that was the point of all this…Pops still teaching me, even after he was gone. The thought made me smile and my pace quickened.

I thought about the list of names as I walked, but those thoughts got me nowhere. Had Pops even meant to include the names with the map? Had he been somehow investigating the disappearances? Maybe playing amateur detective like a character from one of his old pulp novels?It was something I could definitely imagine him doing -- scanning the daily newspaper for details, listening to the nightly news reports -- especially in his later years after he’d retired from the mill.

After just a single misstep when I miscalculated the distance between two towering pines, I easily found where "X" marked the spot on Pops' map. He had hidden his treasure at the base of an old weeping willow overlooking a lily pad-choked pond. It had taken me exactly ninety-seven minutes to find it. More than 20 years after my last treasure hunt, I still had it. I would have to remember to

call Lee later in the morning and do a little bragging.

I pushed the log off to the side and stabbed at the dark earth with my shovel. Just as I expected, it was firm and unyielding. Pops hadn't left the house in four months before his death, so unless he’d had help, he had planned this little adventure many months in advance.

The thought only added to my excitement and curiosity.

I started digging, stopping after just a few minutes to remove my shirt. A fish jumped in the pond. A fat squirrel showed up to watch my progress. A crow cursed at me from the treetops.

I was just about convinced that I was in the wrong spot after all when the shovel hit something that wasn't dirt.

I dropped to my knees and used my hands to uncover what I had found. Once again, feeling time slip away, my dirt-crusted fingers racing faster and faster...

…until they pulled an old cigar box out of the deep hole.

The box was secured with a twist of rotting, black string. I scrambled to untie the knot, my fingers muddy now with perspiration. I could hear a strengthening breeze stirring the trees, and I realized I was holding my breath.

I tossed the string aside and opened the box.

Inside, I found a tangled mound of gold and silver jewelry. Bracelets. Earrings. Necklaces.

And a small stack of driver’s licenses rubber-banded together.

I undid the rubber band and flipped through the licenses.

And then I counted them.

There were nine.

*****

It took a lot longer to make it back to Pops' house. Almost three hours. Nothing looked familiar anymore. I made a lot of wrong turns.

My head hurt.

My heart hurt.

I couldn't stop thinking about the nine women.

I couldn't stop seeing their faces on those driver's licenses.

And I couldn't stop thinking about the second map I had found tucked inside that rubber-band with their licenses.