This Month's Oddity in the News:

Modern science detects disease in 400-year-old embalmed hearts

IN THE ODDITIES ARCHIVES

Tapeworm

Wooly Mammoth

Exorcism

Dog Mummies

Black Widow on Grapes

Bitten Ear

Mummy

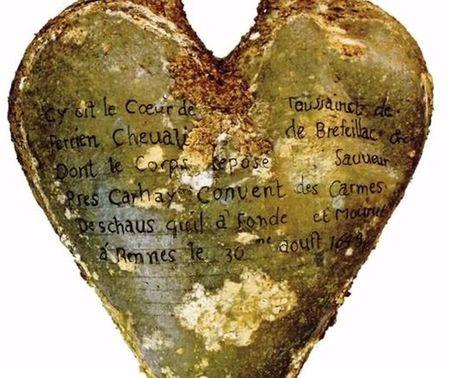

A heart-shaped lead urn with an inscription identifying the contents as the heart of Toussaint Perrien, Knight of Brefeillac, who died in 1649

Reuters, December 2, 2015 -- In the ruins of a medieval convent in the French city of Rennes, archaeologists discovered five heart-shaped urns made of lead, each containing an embalmed human heart.

Now, roughly four centuries after they were buried, researchers have used modern science to study these old hearts. It turns out three of them bore tell-tale signs of a heart disease very common today.

"Every heart was different and revealed its share of surprises," anthropologist Rozenn Colleter of the French National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research said on Wednesday.

"Four of these hearts are very well preserved. It is very rare in archaeology to work on organic materials. The prospects are very exciting."

One heart appeared healthy, with no evidence of disease. Three others showed indications of disease, atherosclerosis, with plaque in the coronary arteries. The fifth was poorly preserved.

"Only one heart belonged to a women, and was totally degraded, permitting no study," said radiologist Dr. Fatima-Zohra Mokrane of Rangueil Hospital at the University Hospital of Toulouse.

One of hearts belonged to a nobleman identified by an inscription on the urn as Toussaint Perrien, Knight of Brefeillac, who died in 1649.

His heart had been removed upon his death and was later buried with his wife, Louise de Quengo, Lady of Brefeillac, who died in 1656. Her wonderfully preserved body was found in a coffin at the site, still wearing a cape, wool dress, bonnet and leather shoes with cork soles.

The earliest of the urns was dated 1584. The latest was dated 1655.

Mokrane said an important aspect of the study was the finding that people hundreds of years ago had atherosclerosis.

It is a disease in which plaque made up of fat, cholesterol, calcium and other substances builds up inside the arteries. Plaque hardens over time and narrows the arteries. Atherosclerosis can trigger heart attacks and strokes.

"Atherosclerosis is not only a recent pathology, because it was found in different hearts studied," Mokrane said.

The researchers cleaned each of the hearts, removed the embalming material and examined them with MRI imaging, CT scans and other methods.

Archaeologists excavated the Jacobins convent in Rennes from 2011 to 2013. It was constructed in 1369 and became an important pilgrimage and burial site from the 15th to 17th centuries. About 800 graves were found, Colleter said.

The research was presented at a meeting of the Radiological Society of North America in Chicago.

See the entire article HERE

About Rennes: Rennes's history goes back more than 2,000 years, at a time when it was a small gallic village named Condate. It was one of the major cities of the historic province of Brittany and the ancient Duchy of Brittany. After the French Revolution, Rennes remained for most of its history a parliamentary, administrative and garrison city of the kingdom of France.

WHAT IS ATHEROSCLEROSIS?

Atherosclerosis -- hardening and narrowing of the arteries -- gets a lot of bad press with good reason. This progressive process silently and slowly blocks arteries, putting blood flow at risk.

It is the usual cause of heart attacks, strokes, and peripheral vascular disease; what together are called cardiovascular disease. It is the Number 1 killer in America, with more than 800,000 deaths yearly.

How does atherosclerosis develop? Who gets it, and why?

Find out HERE

OTHER STUDIES OF MEDIEVAL REMAINS

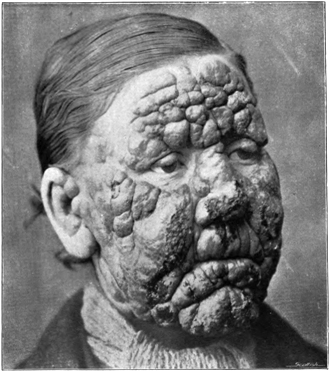

The genetic code of leprosy-causing bacteria (now known as Hansen's Disease) from 1,000-year-old skeletons has been laid bare.

Similarities between these old strains of the bug and those prevalent today have given scientists unique insights into the spread of the disease.

It has revealed, for example, the key role played by the medieval Crusades in moving the pathogen across the globe.

See the medieval leprosy article HERE

Oldest case of Down’s syndrome from medieval France

The oldest confirmed case of Down’s syndrome has been found: the skeleton of a child who died 1500 years ago in early medieval France. According to the archaeologists, the way the child was buried hints that Down’s syndrome was not necessarily stigmatized in the Middle Ages.

See the article HERE