This month's Morbidly Fascinating topic:

The Radium Girls of 1917 to 1926

IN THE ARCHIVES:

Shrunken Heads

Dissections

Alberta the Dog

Synthetic Cadavers

Cobain and Depression

Preserved

Heavenly Bodies

Open Caskets

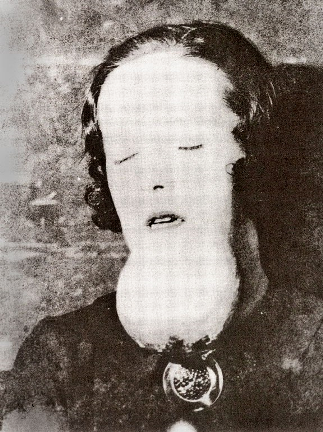

Photos above: Grace Fryer before and after radium poisoning (post mortem)

Side view photo of Grace Fryer (post mortem, above)

Woman working in the radium factory

Workers in the factory

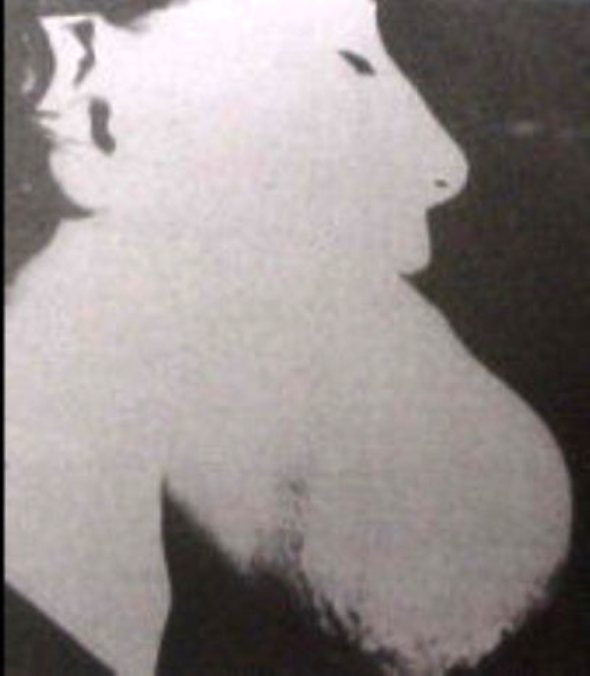

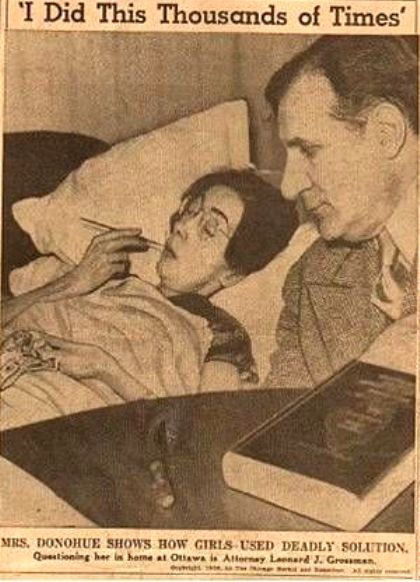

From her hospital bed, Mrs. Donohue shows how girls often licked the brushes used to paint radium on the dials...this practice would make the brush tips more pointed and therefore their aim would be more accurate

Two contemporary newspaper articles

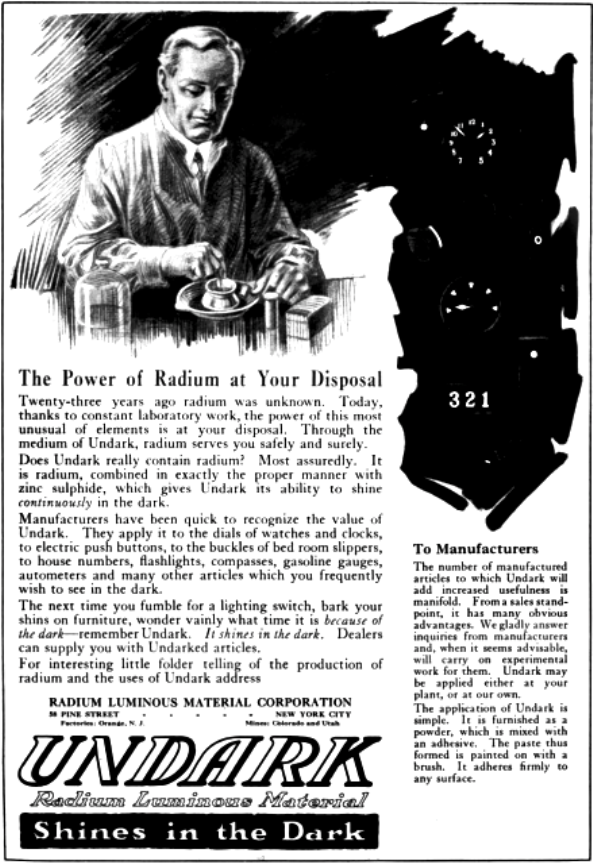

Undark Advertisement

Unidentified man suffering from radium poisoning

Radium poisoning sometimes affected other areas of the body as well

See more about The Radium Girls HERE

Who was Grace Fryer?

Grace Fryer worked in a factory that made the first watches with illuminated dials. These dials were painted with radioactive paint which the all-female painting staff hand painted. To keep their paintbrushes well pointed, they would put the brush tip in their mouths. Grace and a number of the women she worked with became the first recorded American industrial poisoning incidents on modern safety records. The radioactive material eventually built up in the bodies of the women and nearly all died of radiation poisoning.

She was the first of the five 'Radium Girls' who banded together to sue US Radium.

Together, there is a recorded total of over forty clock factory workers who died from probable radium poisoning.

Excerpt from Kate Moore's book, THE RADIUM GIRLS

On the morning of 15 October 1927, a dim, autumn day, a group of men foregathered at the Rosedale cemetery in New Jersey and picked their way through the headstones to the grave of one Amelia — ‘Mollie’ — Maggia. An employee of the United States Radium Corporation (USRC), she had died five years earlier, aged 24. To the dismay of her friends and family the cause of death had been recorded as syphilis, but, as her coffin was exhumed and its lid levered open, Mollie’s corpse was seen to be aglow with a ‘soft luminescence’. Everyone present knew what that meant.

‘My beautiful radium’, Marie Curie called the element she discovered in 1898. She was in thrall to it: it stirred her, she wrote, with ‘ever-new emotion and enchantment’. As she shared her discovery with scientists, and radium was found to be capable of destroying human tissue, it was enlisted in the battle against cancer — and not just cancer but fever, gout and constipation. Some claimed it could restore vitality in the elderly. Others took to drinking radium water, or visiting radium clinics and spas.

These treatments were strictly for the rich — gram for gram, radium was the most expensive substance on earth. But when radium-dial-painting ‘studios’ were set up in Newark, New Jersey, and Ottawa, Illinois, hordes of working-class girls, some as young as 14, applied for jobs painting luminous numerals on watchfaces. The work was congenial. They sat in rows, dipping fine camelhair brushes into a radium solution, then ‘pointed’ them between moistened lips before painting the numbers on the dials. After Congress voted America into the war in the spring of 1917, most of the dials were for military use, so the girls had the satisfaction of knowing they were serving their country. They were also extremely well paid: up to three times what they might have earned in factories.

And then there was the glamour of working with radium. Everything it touched glowed. If the girls blew their noses, their handkerchiefs glowed; they glowed like ghosts on their way home; their clothes glowed from their wardrobes at night. Some girls wore evening dresses to work so that they would glow on their dates. One painted her teeth to impress her man. There was no reason for them to think this was in any way sinister — rather the reverse: ‘Radium will put rosy cheeks on you’, they were told.

It took time for the girls to sicken. Some, like Marguerite Carlough and Hazel Vincent, suffered chronic exhaustion. Others, like Albina Larice, produced stillborn babies. For many, like Mollie Maggia, it started with severe tooth decay. The dentist would remove the rotten teeth, already practically falling out of the girls’ mouths, but the gums wouldn’t heal. Instead, agonising ulcers sprouted in the holes left behind. Very often their jawbones crumbled to the touch. The girls’ breath became foul-smelling, and their skin so paper-thin it would split open if simply brushed by a fingernail. Death, when it came, was usually accompanied by violent haemorrhaging.

The first legal suit against USRC was filed in September 1925, but when it came to getting justice the radium companies held all the trump cards. First, there was the variety of the girls’ symptoms: surely they couldn’t all be traced to one source (diphtheria, angina and TB were among the recorded causes of death). Then there was the fact that radium poisoning was not officially a ‘compensable’ disease. And finally there was money: what little the girls had was going to pay doctors; there was nothing left for lawyers.

In the end, it took a remarkable lawyer, Leonard Grossman, willing to work pro bono, and an extraordinarily courageous dial painter, Catherine Donohue, prepared to fight the cause literally to the death, for justice to triumph. After eight appeals, victory came on 23 October 1939.

See the article HERE