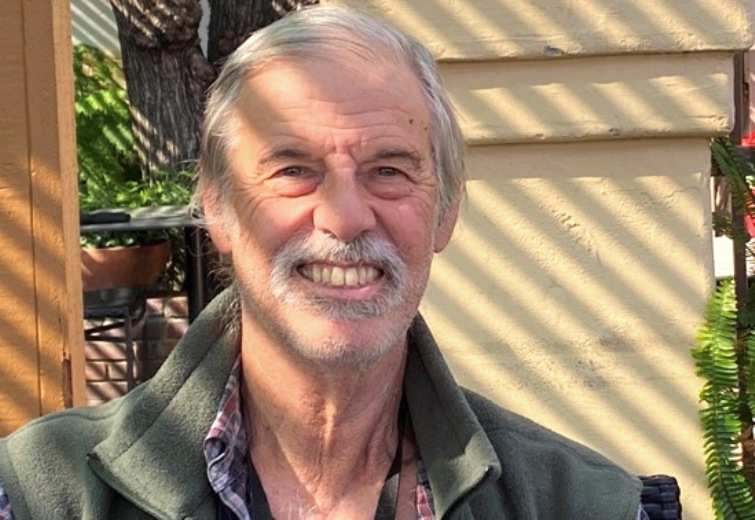

FICTION BY GARRETT ROWLAN

Garrett Rowlan is a retired Los Angeles substitute teacher and the author of two published novels and 70 or so short stories. His website is HERE

RIVER OF LEAVES

by Garrett Rowlan

The sound came on a Saturday afternoon. Because I was napping, I woke annoyed. The gardeners were not supposed use their leaf blowers at this hour on this day. I should know; I helped to write the legal code for my very large homeowners’ association. As a woman, I was proud of the lack of gender discrimination in the association.

The leaf blower rule was written to suit pool parties, because no one wanted the noise and the dust. I have no pool nor throw any type of parties, but I hate leaf blowers for another reason.

I sat up, shooed the cat off my bed and left my house to exercise my rights as a member of The Canyon Homeowners’ Association. Outside, I oriented myself to the sound and went north toward Kellogg Park, named for the millionaire who had developed this area of mostly Spanish-style houses in Glendale, California, back in the Twenties and Thirties. His estate, now a rest home, was the only commercial property on an otherwise residential-zoned community.

As I walked, the canyon walls created echoes. Confused, I veered to a side street just below Kellogg Park. There were leaves scattered up ahead, and I intended to tell the violators just what the rules were: No leaf blowers after noon on Saturdays.

Just then a truck came roaring out of a curve in the road, the driver almost fleeing in his gas-guzzling, smog-producing pickup. From the sides, leaf blowers hung like infantry weapons. He sped off while giving me the briefest of glances; a man with sunglasses and a baseball cap and looking like an artist’s depiction of a murder suspect.

Soon, I saw a small, impromptu exemplar of land art. Through the medium of sycamore, liquid amber, and oak leaves, plus small sticks, an image formed on concrete: three men and a woman clutching a child’s hand. They were heading north across a river of leaves.

A breeze kicked up, and a miniature cyclone blew the images into a tiny tornado. They whirled and as I covered my eyes against the dust, I thought I saw the child in the picture, the land-art or whatever it was, turn to me.

It was a child’s face made of sticks and leaves, and it was me, my face, as a child.

I convinced myself it was a hallucination or a Rorschach-like construction from worry over my mother’s health. I went point-by-point, as if I were arguing to a jury. I had been thinking about immigration, I reminded myself, and my mother, with whom I crossed the Rio Grande years ago.

That night, I received a phone call from my sister. “Her neighbor can’t watch Mom tonight,” Marie said, “and I have to work late. I wonder if you could watch her?”

I didn’t like to go into East Los Angeles. I asked, “How is she doing?”

“Not too good,” Marie said. “I think her mind is going. She speaks of some Curandero who didn’t do a thing for her. She just got this thing into her head.”

“Oh, a shaman. Where did she find him?”

“Who knows,” said Marie, the joker. “Maybe the yellow pages.”

“Yellow pages,” I said. “Are they still around?”

“Only for Curanderos.”

That evening, I drove from Glendale to East Los Angeles and pulled up outside a house with a cinder-block wall that mother had put up as a buffer. Micaela, the neighbor, came from the adjoining house, a worn woman with a limp, and gave me the key.

“I’m going to a church function,” she informed me, “I should be back before ten.” She pivoted and left. I don’t think she liked me for various reasons. I was an Episcopalian, for one thing, converting to please my ex-husband’s parents.

Entering the house. I found Mother in the back. A dim night light glowed beside her bed. Beside it were various medications, which I suspected she took out of consideration for us. She was a religious woman and believed that something better waited beyond, provided that one made a decent resistance to death, including I suppose a Curandero just to cover all the bases. I settled beside her and touched her forehead. Her eyes opened.

“Xochitl,” she said. She had never called me anything else. “Sandra,” had been an insult to her.

“I’m here.”

“I’m glad,” she said.

She closed her eyes, her face like a death mask in repose.

“How are you feeling?”

She nodded, ambiguously, and nodded off. She’d been sleeping a lot lately, Marie had said. I went to my book, a legal thriller by Scott Turow, but soon, on a hunch, I went out to the garage. I found, under a cover, a leaf blower.

I touched the device, remembering the way my father (who worked for a gardener and eventually owned the business) couldn’t resist strapping it on, though it bent his aging back. “Try it,” he told me once, and I had dutifully sent a few leaves flying. He laughed. “You act like you’re holding a flamethrower.”

It had a dirty, ignored, dead-insect look in the dim garage light, like some lab experiment gone wrong. Papa has been dead ten years, and this was what remained of him, this thing no one needed. Picking it up and putting it down, I brushed my hands clean.

I recalled what he had said to me, shortly before he passed on. “You keep your leaf blower in good condition,” Papa said, “and it won’t let you down.”

I didn’t exactly disdain his message, but I suppose I treated it with contempt, a superiority of logic, because I had just passed the bar exam.

It was shortly after that I married Martin and changed my name. Mom didn’t like that.

“You should be proud of your heritage. It’s all we really have.”

Yet I had had enough of my heritage, which as far as I was concerned was this small house off Soto in East Los Angeles where my mother still lived. Back then, I had to share a room with my younger sister—my brother, younger still, got the other room all to himself—with a postage stamp of a backyard. It abutted an alley of foot traffic restrained by a concrete-block wall. My mother and father had the room in front, though after a quarrel one of them would sleep on the couch. I married to get out of it. Which probably explained my divorce years later.

Long ago I decided I would get out of poverty; it was why I strove for success. That included good grades, college (the first in my family), and finally an upscale marriage. The name change included changing Xochitl to Sandra, the last name Rodriquez to Rollinson.

I focused on the leaf blower in my hand. I thought of the portrait in leaves I saw that afternoon, three people crossing a path of leaves.

Soon the phone rang. It was Uncle Bobby, calling from the high desert, where he had lived since he retired. He’d been a Beverly Hills tailor for forty years, did a lot of film work too, before his elegant hands got too shaky to hold a needle.

“How is she?” he asked.

“She’s resting comfortably,” I said.

He asked me how I was doing. I said I was doing okay. (Except for autumn leaves forming bodies on the ground.) I asked Bobby how he was. He said he had trouble sleeping. “Old man stuff,” he added. There was another pause. There always were pauses with Uncle Bobby, the weight of something unsaid. “You let me know if there’s any change, okay?”

“Of course,” I said.

“I’ve always been so proud of you,” he said. “When I think we almost lost you.”

“Crossing the Rio?”

“Yes,” he said, “The current pulled you back.”

“I almost died. I was sick for days.”

“Yes,” he said, “we wondered if we took you from the Rio only to have you die of a fever, but you pulled through.”

“Bobby,” I said, “did you know mother was seeing a Curandero?”

There was a pause. “No,” he said. “Who was it?”

“I don’t know.” I wanted to tell him what I saw this afternoon, but I was afraid he would think I was becoming old and lonely and seeing my face in a pile of sticks and leaves. And I hoped I was.

Later, Mother slept, her soft snore seeming to match the candle’s gentle flutter. I strolled around the house, a small house and yet, in a way, spacious to me, perhaps because I remember it being full of people as I grew up, my parents and my siblings, my sister and my brother, Javier. His dreams of making music became drugs, became AIDS. He’s now one of the ghosts.

“How is she?” Micaela asked, coming back at ten.

“She’s fine,” I said.

“Good.” She held out her hand for the key. I know she didn’t like me, how I married a gringo and changed my name and moved out of the community, as if East LA was some sort of plague-ridden wasteland. Micaela was unhappy, I heard, that I got the house in the divorce; a much nicer one than this.

“How’s everything?” She had a mean, curious slant to her head.

“Oh,” I said. “You know.”

She made an expression as if I had just proven her point. People that turn their back on their family and community—as she once accused me of doing—don’t end up well.

I smiled tightly and left.

Next day, I heard the leaf blower again. I left my house. I went north and near the local park with its flowers and oak trees, I saw a man wearing goggles and a bandana around the mouth as the leaf blower whirled the leaves around him as if he were a figure on an old map, blowing ships across the Atlantic. The leaves seemed to herd themselves at the moment he turned off the device.

He walked away and I went after him, but when I looked down I stopped at what he made. The leaves formed a ribbon that undulated to suggest the flow of water. Crossing the river of leaves—it was the same three adults and the child who was me.

I watched, horrified and fascinated, as the leaves and the dust and the branches and flowers swirling to suggest that each figure moved forward except for me, as I lost my grip on my mother’s hand and slipped back into the current of sticks.

And by the time I pulled myself away from the scene, the man had climbed in and started his truck. I ran after him, shouting, but he didn’t hear.

I turned at a whirling sound. A gust erased the picture. The leaves blew down the street and to the hills beyond the Kellogg House. I started to feel as if I were made of leaves myself. Dust to dust, ashes to ashes, I felt as if those words were spoken over me as a gust blew me away. And maybe I might have disappeared right where I stood when a woman spoke.

“Sandra!” she said. “Are you all right?”

It was Bertie Marks. She lived across from the park, and I knew her from the Canyon Homeowners’ Association.

“Fine,” I said, I came back to myself as if blood were poured into my veins, “I was just looking at the leaves, the way they formed shapes on the ground, human shapes.”

“Yes,” Bertie said uncertainly, “I guess they do, if you have a mind to see that way.”

I walked home, feeling weak and I was sitting on my couch, trying to understand, when the phone rang. Stunned, I only answered just before the machine picked up. It was Marie. She had gotten a called from Micaela.

That night, after we left the hospital, weeping and hugging, I came home, went to bed, and dreamed of insects riding the backs of brown-skinned men. One of the circular shells popped open to let a baby fall. It cried on asphalt. Mother emerged from the house and picked up that bawling infant and asked me if it were mine, and that’s when I woke.

*****

The funeral was in Rose Hills, out in Pico Rivera, southeast of LA, the downtown skyscrapers to the north. There were a dozen people gathered.

I hadn’t been well since my last encounter with the leaf blower and the man or demon that pushed the leaves into a semblance of my childhood body, as if I had become something shaken from a tree, dust and branches and fallen leaves. My limbs now ached as if I had aged thirty years almost overnight.

I wondered if my ex, Martin, was taking his revenge on me. He’d never gotten over the divorce, despite marrying someone younger and having two children by her and prospering himself. Such is the way of some lawyers; we hate to lose, especially to a former spouse.

Sometimes it felt hard to draw a breath during the funeral, as if my lungs were waterlogged. I almost gasped as Bobby spoke of coming up from Mexico so many years ago, seeking a better life. And how the water almost took me away, Mama diving to save me.

Later, at the graveside, I saw in the distance a man I didn’t know. After the service I went to him.

The man was Latino, with long hair combed straight back except for two tiny braids on either side that dropped from under the black beret. He wore a choker of white beads. His eyes were small and hard, like black shoreline pebbles.

“Who are you?” I asked.

“Have you ever noticed,” he said, “how funerals sometimes come in twos?”

“Who are you?”

“As the person mourning over a grave were mourning over herself, or the corpse she’ll be soon.”

“Who are you!”

“I’m someone whose power comes from Quetzalcoatl, the God of wind.” He said this in an officious tone, as if presenting his credentials.

“And who’s this queasy God?” I asked, deliberately mangling the word that I had never gotten quite right anyway.

“Quetzalcoatl works with the wind,” he said. “It’s an old god, very old, and like all us old people he sometimes needs a little help. We all need a little help.”

“Like a leaf blower?” I turned away, feeling queasy myself, and not wanting to spend another second in the presence of this creep.

When I turned back to look, he’d vanished.

*****

Later, Marie and I went through Mom’s house: What to throw away, what to keep. In the garage I found the leaf blower. I have no idea why I wanted to take it home, hating it as I did…maybe because it seemed to carry my father’s spirit, however remotely.

I took it home and cleaned it, polished it, put gasoline in and even started it just to see if it worked. I remembered what Papa said about it, how it would never let me down.

That night, I lectured at Cal State—I taught two nights a week—and I was exhausted. In fact, I could barely stand on my feet or stay awake as I drove home through a breeze. I didn’t know what was wrong with me but I figured it had to do with the river of leaves and how I was drowning into dust inside it.

Inside my house, I changed into jeans and a sweater and had a small glass of wine and listened to the wind gust and ebb, gust and ebb. The cat regarded me with a suspicious stare, as if I were old food he refused to eat.

The wind blew harder outside, shaking the leaves of the Sycamore in my front lawn.

In the distance, I heard the sound of a leaf blower, though it was after ten at night. The sound seemed to bore right into me, turning my veins into dust if I didn’t do something.

I stumbled outside weakly, my hand against the garage wall for balance, and took the restored leaf blower from the garage. I fired it up. When I did, I heard an answering sound from up the canyon, up near the Kellogg House—a distant sound like a delayed echo. It was a challenge.

I shut my leaf blower off. Though staggering under the weight, I strapped it on and headed that way to accept the challenge, whatever the challenge was.

As I walked, the sound of the blower grew louder and I thought someone would step out of their house and investigate the din. No one did. Maybe only I heard it.

In a couple of blocks, I entered a lit, parking area near the Kellogg house. Leaves rattled on the ground with a metallic cadence as, like a flock of birds coming to rest; they arrayed themselves on the concrete in a palette of greens and browns.

Beside them, the man with the leaf blower stood and fired up his instrument. I couldn’t tell who he was. Perhaps he was the Curandero at my mother’s funeral—the man I had seen driving off from “painting” my image on the ground—or perhaps it was my ex-husband, Martin having found some avatar that could escape the legal or physical restrictions and do what he wanted to do to me for years, which was to grind me into dust.

I fired up my leaf blower and aimed it at the man as he aimed his at me, a shootout at near midnight. I felt the blast of a thousand hurricanes but somehow the air that spewed from my nozzle seemed to hold me together,

I screamed in resolution and held the leaf blower firmly in his direction. It was then I realized the breeze coming off him really did come off him, first the hair and the skin and finally pulverized bones, ending with a mouth that gave a last scream of agony before the teeth turned to dust and collapsed, leaving nothing there.

I turned off the leaf blower. In the faint light coming off the Kellogg Estate, I saw there was nothing left of him but shattered parts and the stick-and-leaf outline of a body that soon blew away, another breeze coming up the canyon.

I felt a new, fresh spring in my step as I turned and walked back to my house.

“You know it’s illegal to run those things this late at night,” someone said as I passed by.

“It won’t happen again,” I said, smiling as I headed home.