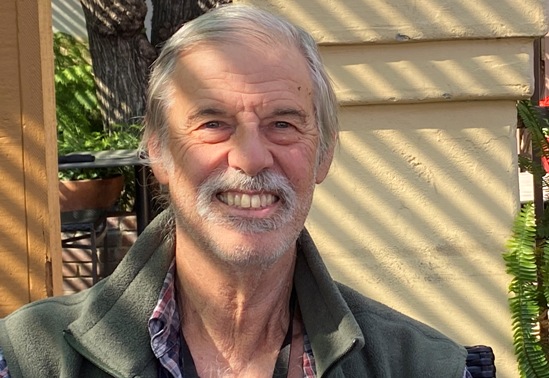

The December Editor's Pick Writer is

Garrett Rowlan

Please feel free to email Garrett at: garrettrowlan@att.net

ELECTROLYTES

by Garrett Rowlan

September fires in Los Angeles County were followed by October’s rain, an early downpour that caused the two lanes of the Angeles Crest Highway to be shut down for several weeks; it had only opened recently. For Herbert and Florence Kipfer of Pasadena, California, the opening was a welcome as was the cool winter’s afternoon. They were San Gabriel mountain people. The beaches…Herbert had already had a lesion removed from his chin. The desert…too hot, and too many wackos fueled on meth and paranoia. No, the mountains were the thing. They were peaceful.

Flo packed a light picnic and they headed out on their trip. It was November and chilly. They passed the Mount Wilson turnoff and winding vistas where the branches of flame-burnt, leafless trees drooped, legacy of the fires this summer. The scorched earth now showed a promising undergrowth of green bestowed by the recent rains.

Herbert spoke fondly about teaching high school as he drove. He reminded Flo that he had often lectured on destruction and resurrection, both part of the same process. “Death and rebirth are one and the same,” he had told his students, who were close to neither.

Those words, repeated, brought a sly chuckle from Flo. “Or so you hope,” she reminded him.

“True,” Herbert said. He recently recovered from surgery. Of death he was certain; of his rebirth, less so.

Changing the subject, Florence recalled the plumes that the flames had sent skyward last summer; the eerie clouds of smoke hovering by day, and the red scars visible by night.

But today there were no fires. Their car ascended under a cloudless sky, blue with a radiance of white at the edges. They reached Inspiration Point, elevation 7385 feet, and pulled off the road. They stepped outside. Florence had prepared a light meal, sandwiches and hot tea. They ate at an iron bench whose surface was textured in a wicker pattern to prevent graffiti.

Looking up across the two-lane mountain highway and, atop a few hundred feet of slope, they both noticed that there was something resembled an enlarged golf ball resting on the ground. Beside it was an outcropping like a gigantic trumpet, its bell pointed toward the sky. It must have been some kind of radio transmission site. “I’d like to hike up there,” Herbert said.

“Now?” Florence asked.

“If not now, when?”It was the question that often underscored their discussions. Herbert had the cancer scare, and Florence had the heart valve issue. They both took medication. His parents and older brother had all died around this age.

“Are you sure?”

He nodded, and Flo smiled to herself. She had learned to tolerate these little enthusiasms of his.

As they cleaned up and put their belongings back into the car, she thought of the golf clubs she had taken from the garage and given to their son-in-law, and the piano that had been sold. She knew the drill. He’d only go a little way, get winded, or bored, and turn back.

He took the binoculars and slipped them on a plastic cord around his neck. He took a notched walking cane he was proud of, having carved it himself. It had a curved end for his hand. Finally, he zipped the beige windbreaker to the neck, as if they were about to venture into Arctic air rather than the crisp oxygen of the mountains above Los Angeles.

A Subaru veered into the turnoff where they sat. A man with a black beard stepped out. He wore sunglasses, ill-fitting pants—too big and too long—and had a nervous twitch about him, as if he were suffering little insect bites here and there. He pulled out a handheld device he checked, as if searching for a signal. Something about him seemed off to Flo, but of course Herbert was his careless self.

“Say,” Herbert asked, “what’s that thing over there?” He pointed upward to the bell-shaped object atop the neighboring slope.

The man said something in a language neither of them understood, just before his handheld chimed. He turned away from them. Herbert and Florence looked at each other and shrugged. They crossed the highway and set out upon the trail.

The man called something.

“It sounded like he said, you shouldn’t,” Florence said.

“Oh, who knows what he said,” Herbert muttered. He led the way, his chin thrust forward and his cane digging divots. His breath soon labored, as Florence knew it would. After a hundred uphill feet, he stopped.

“Time to go back?” Florence said.

He looked down. “Sticky monkey,” he said, touching the tip of the cane to a green shrub. “Sage,” he said, moving a few steps on. “Hawthorne,” he said, going even farther and pointing at another shrub. Florence didn’t say anything. The naming of things was a way of both asserting himself and taking cover; there was safety in identification.

Continuing, they wound around the hill, occluding the view of their parked car. First step in leaving civilization is when you can’t see your car, Florence thought.

Herbert stopped where the trail ascended toward the odd structures. From this side, they saw more clearly the chain-link fence around its base.

“Shouldn’t we go back?” Florence said.

“Give me a minute,” Herbert said, catching his breath a second time.

From the trail ahead of them, they heard a dog bark, a loud sound with a metallic ring, like someone whose larynx had been damaged. The dog rounded the bend ahead of them. Its motion was odd, bouncing as it ran, a seesaw with legs.

As it came closer, they saw how its eyes were little cabochons of blue intensity, and its two ears sharply lifted like matching antennae. It was a poodle of sorts with its black hair twisted, almost braided. They prepared for the dog’s crossing into their space, but it stopped. Maybe it was the cane Herbert held. The dog rocked back on its haunches.

“Doggy,” Herbert said, a note of inquiry in his voice, as if to say, what breed are you? He stepped forward, approaching it.

“Herbert,” Flo said sharply, “I don’t think you should.”

It looked up, panting. Herbert bent and extended his hand. A blood-red tongue spilled and licked. The tongue withdrew as if finding something strange about human skin.

They heard a clapping from up the trail. The dog whirled and bounded with that oddly rocking gait toward a tall, bald, thin man with a long forehead and deep-set eyes, pale as low beams on a foggy day. He approached them. In the chilled, late winter afternoon he dressed in a T-shirt and wore no shoes. His gray pants were torn in places.

“Are you one of them?” the man asked. Flo couldn’t place the accent. There was a Nordic crispness she detected, but something else too.

“One of whom?” Herbert replied.

“People I don’t want to see.” The man’s look of alarm faded. He smiled, revealing two missing teeth. “You’re not them. I’m glad. How are you?”

Herbert ran a handkerchief across his forehead, damped by the slight climb. “Fine,” Herbert said. “I need to wet my whistle.”

“You need to what?”

“I’m thirsty, that’s all. Forgot to bring water.”

The man’s pants were secured by some kind of utility belt with notches from which he removed a small plastic container. The top he cracked open with an upward flick of his thumb. “Drink this,” he said, stepping forward and holding out the bottle to Herbert. Herbert took the bottle and hesitated. He could sense Florence behind him, disapproving.

The man smiled, his lips widening. “It’s water,” the man said, “with electrolytes.”

“Herbert!” Florence said.

Herbert drank. “Tastes kind of acidic,” he said. “But not bad.” He took a second drink.

He offered the bottle to Florence, who shook her head. He handed the bottle back to the man, who took it, capped it, and slipped it back into his belt. “Thank you, that was good, Mister—”

The man, however, pivoted abruptly and walked away. The dog followed him with that odd, rocking-horse gait.

“That thing up there,” Herbert called after him. Above them, the man and the dog turned in unison. “What is it?” Herbert pointed.

“It’s radar,” the man said.

“Strange-looking thing,” Herbert said.

“It has many uses,” the man said. He nodded and moved on.

“Why did you drink that?” Florence asked. “Who knows what was in that bottle.”

“I don’t know,” Herbert said, and he looked genuinely puzzled. “I just felt like it.”

“Let’s go back,” Florence said.

“No, I feel better,” Herbert said. “That water did the trick. I’d like to go on a little farther.”

“I don’t know if that’s a good idea. I mean, he’s nice enough but there’s something about him…and that dog.”

“An odd breed, I agree.” Herbert made a self-indulgent smile. “It’s just a little farther, Florence. We’ve got a little light left. You’re always telling me I need exercise.”

“We go up there,” she said, “and we come right back.”

He turned and headed up. She hesitated and followed. He had gone perhaps another hundred feet when he stopped. She thought he was going to reconsider when he said,

Instead he asked, “Look—what do you think that is?” He pointed to a high slope a mile away. He raised his binoculars.

Florence squinted but couldn’t make out anything. It was something that looked like a ski lift. It was hard to tell because the background was to the east, where a purpling effect made it hard for her to discern anything.

“Can’t really see anything from here,” he said. The binoculars wobbled in his hand as his feet in their New Balance walkers kept shifting in the uneven, slanted ground. His walking stick he moved for purchase.

“Herbert,” she began.

He didn’t hear her, or pretended not to—a Herbert technique, she knew—and he continued walking. “Let’s go,” he said, and with a new spring in his step, or so it seemed to her, they went upward.

The tall man and the dog had vanished around the slope up ahead, taking another fork in the trail that disappeared in the direction of the ski lift or whatever it was in the distance.

Herbert had always been the more adventurous, Florence knew. He had started his teaching career in one of the worst schools in Los Angeles. “I survived Vietnam,” he had said at the time. “I can survive this.” He did. He believed that it would get better, and it did. He retired with a handsome pension. Florence had been a legal secretary, and over the years had learned how a little misadventure could turn into something costly.

They never had children. They never wanted to find out why, only because of the implied blame. Anyway, they had each other. Only it was sometimes sad—she knew Herbert felt it—that they had no stake in the future, no future at all.

In another ten minutes, they rounded the bend and came to the structure they had seen from the highway below. Up close, it did not seem so mysterious, simply a government station surrounded by wire and warning signs. The oversized sphere and the large trumpet bell nearby now looked less alien, only shapes reflecting some complicated technology. In the middle of the fenced-off space was an antenna, a few feet high.

“Things aren’t always as impressive up close,” Florence said.

“Still, the view,” Herbert said. He had turned away and pointed his binoculars to the west, toward the fading sun. “I’m glad we came.” He lowered the binoculars.

“So am I,” Flo said. She meant it because the strange man and his dog had disappeared. “But now I’d like to leave.”

“I wonder where that fellow went to,” he said. “That was some sip of water he gave me, perked me right up.”

“It contained electrolytes,” she said.

Herbert walked up to the fence.

“That’s a funny sound,” he said. “Hear it? It’s sort of a buzzing. Do you hear it?”

“No,” she said. “Let’s go back.”

As she turned, taking his elbow, his knees buckled. The walking stick fell from his grasp and hit the ground. “My head hurts,” he said. He dropped to his knees and opened his mouth and emitted a groan of agony that was high-pitched and almost soundless, almost inhuman. He drooled, dropped to all fours, looked like he was going to vomit as a shuddering went along his body.

“Herbert!” Flo cried. She bent down next to him.

His face was pale and his features slightly askew, as if he were suffering a stroke. “It’s coming on again.”

“What is it?” she asked. “Is it your heart?”

“No, my head. It feels like it’s…breaking.”

She fumbled in her jacket for the cell phone. As she did, she happened to look up and see, coming from the disused ski lift a mile away, the on-off flash of a light.

“Don’t call 911. Just give me a second,” Herbert said. “Now the pain is going.” He waved her away. “Just give me a little space.”

She backed up to the cliff’s edge. From here she could see their car and the other car next to it. The bearded man was there. He held something to his ear like a walkie-talkie. She couldn’t quite tell what it was, even using Herbert’s binoculars.

She lowered the binoculars, turned, and raised them again. This time, in the distance, she saw on the opposite slope small, stick-like figures moving quickly. Lowering the binoculars, she wasn’t sure what she had seen. She didn’t want to see more. She was unsettled by a sense of symmetry of events, the bearded man, the man with his dog, and whatever was occurring with the stick-like figures in the distance.“I’m calling an ambulance.”

Herbert leaned over and picked up the fallen stick. “Wait,” he said. She saw the color return to his face. “It passed. I’m better now. The pain is gone. That was intense. It felt like my head was cracking. It’s gone now.”

Still alarmed, Florence said. “What was that?”

“I don’t know. It was a headache, but it passed.”

“I want to leave. Now.”

He nodded. She offered a hand, but he sprang to his feet in a way he hadn’t done in years.

They left. As they were going down the man with the odd dog came walking out of the ridge to their left.

“Howdy,” Herbert said.

“Are you all right?” the man asked.

“I’m good. Had a little incident there but I’m okay. Those electrolytes really did something to me. Picked me up and knocked me down again.”

“And how do you feel now?”

“I feel pretty good,” Herbert said, as if surprised himself.

“I’m happy to help,” the man said. He smiled, his lips pulled back on invisible hawsers.

“You call that help?” Florence demanded. She was about to add something when she saw the dog trotting down the trail. The dog barked once, as if to say yes.

“Herbert,” Florence said, “we should be getting down that trail. It’s going to be night soon.” She tugged at his sleeve.

“Yes,” he said. He turned to the man. “It’s going to be night. Are you staying up here?”

The man didn’t respond. Herbert waited. Clearly the man didn’t want to talk. He had turned in the same direction the dog was looking.

“Herbert,” she said. She had always loved him despite his faults, one being a lack of social sensibility, a certain blindness of perception. He could read body language in a classroom, but in parties of his peers he was sometimes awkward, something he tried to correct by drinking, which didn’t turn out well.

“Where are you from?” Herbert asked the man. He didn’t answer. “We’re from Pasadena ourselves.”

The man only nodded. He kept looking along with the dog.

“We should leave,” Flo said. Again, she tugged on Herbert’s sleeve and half-turned, as if by the weight and gravity of her body she could induce him to walk down the trail. Near the ski lift, that single light blinked. It was now green. The dog gave off a brief yelp of recognition. It then turned and looked down the slope at her.

“Herbert,” she said, “I’ve had enough. I’m leaving.”

“She who must be obeyed,” Herbert said, who liked to cultivate a henpecked air when it suited him. The man only stood and watched.

They descended. Ten minutes later, they rounded the bottom of the hill. She saw their car, fifty yards away and looking like a refuge in the dying light. The bearded man remained behind. He was wearing headphones now and listening intently.

Herbert stopped. “Give me a second here, Flo,” he said. He was breathing heavily.

“Are you okay?” she asked.

“Yes,” Herbert said. He leaned against his stick. “I just…I just felt strange there for a second.”

With a deep breath, he resumed walking but there was something odd about his gait. It was jerky, one leg dragged, and his mouth sagged open.

“I’m worried about you, Herb,” she said.

“I’ll be fine,” he said, weakly. They made the highway. He stopped and patted a fist to his chest.

“Are you okay?”

“It hurts a little,” he said.

“Your heart? Maybe it’s the lack of oxygen. Let’s get you down below.”

“Yes, Mother,” he said.

Mother? she thought. Where did that come from? Herbert had disliked his mother. His father he’d worshipped. Slowly, they crossed the two-lane road and entered the parking lot. His walking stick hit the ground like a dull hammer. She wondered where the nearest hospital was.

He stopped. He winced and buckled and fell to the ground. The walking stick clattered beside him.

“Herb!”

He lay on his back. His eyes were open, and for a second she feared he had died right there, before he blinked.

“Help!” she called to the bearded man. He ignored her. On the other side of the parking lot, he worked his handheld, adjusting a signal or something.

“Help!” she called again. “Help! Mister, can you hear me?”

The man looked at her as if annoyed. Abruptly, pivoting from the waist alone, Herbert sat up, and a moment later rose to his feet.

“Stop it, Herb! You’re scaring me!”

Herbert looked at the bearded man, who had resumed looking at whatever he held and the signals it was sending through his headphones.

“Herbert,” she said, “I’m calling an ambulance.”

He ignored her. Dragging one leg, and his mouth open, he headed in the bearded man’s direction. He held the stick not by the curved handgrip but the rubber end that cushioned the pavement’s impact.

“Herb?” she said.

“Hey fella,” Herbert said, and struck the man behind the ear. The headphones slipped around his neck. The second blow caught him on the shoulder. The third blow buckled his knees. The fourth popped a tooth, as if Herbert swung a cudgel. The fifth blow brought blood. The sixth made him fall.

“Herb!” Florence screamed, running up to him. “What are you doing? Stop it!”

He swung the cane and caught her across the cheekbone. She fell to her knees. She put a hand to the point of impact, felt a bruising and a flow of blood. Through her parted fingers she saw the bald man running down the slope with the dog in front of him. They were dim figures against the dark eastern sky.

Herbert turned back to the bearded man and swung again and again. One eye popped from its socket. His fingers were twitching. The cane Herbert had used had snapped in half. He was kicking the man and then stomping on him with the leg that had dragged but was now as strong as a battering ram, or so it seemed by the sound of breaking bones and blood.

“Herbert!” she screamed.

He advanced. She rose, trying to escape, went a few steps, and fell. When she looked up Herbert was standing over her. Looking down, his eyes were lighted blue discs. Beyond him, the bald man was dragging away the body of the bearded man, and the dog was licking the blood.

“Herb,” she said. She was fighting back tears. “Why? I don’t understand.”

“I feel good, Flo. I feel better than I have for ages. These fellas have big plans and I want to be part of it.”

“You killed a man, you…”

She felt her heart pounding and wanted her medication. The bald man slammed the door of his car shut and he and the dog came to her. The three of them looked down at Florence.

“She’s ready,” Herbert said.

The man unhitched the water bottle from his belt. He uncapped the bottle and bent down to her.

“Electrolytes,” Herbert said.

“They help with the transmission,” the bald man said.

“It helps the radio waves get into your brain,” the dog said. He had a British accent.

“Drink and you’ll feel better,” Herbert said. “I know I do.”

She kept her mouth shut but they forced her jaws open. The water splashed against the back of her throat and she swallowed involuntarily. She tasted its acidic tang and felt something go through her.

Garrett Rowlan lives in LA. He has stories forthcoming in the Hollywood Horror Anthology—his story is about a retelling of “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood”—and in the All World Wayfarer collection of fiction with a nonhuman protagonist. His website is garrettrowlan.com