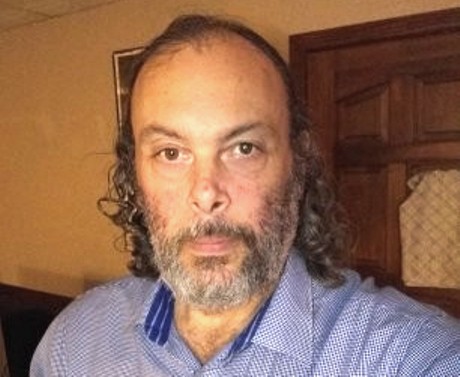

The August Featured Writer is Tim V. Decker

Feel free to email Tim at: deckerti@mnstate.edu

THE END OF THE WORLD IN ANALOG AND DIGITAL

by Tim V. Decker

I was browsing in a records shop in downtown Fargo when I first heard the strange music. It had been playing since I’d entered the store, and I’d been there about a half hour because I wanted to buy something on Vinyl but couldn’t find anything.

Of all the places I went to in Fargo, the record shop was the only one where I didn’t feel exactly welcomed. Maybe forty-year-olds who push homeowner’s insurance for a living weren’t supposed to go there.

The kid behind the counter stroked his well-trimmed beard and stared. I couldn’t tell where his eyes rested because they were hidden behind the reflection of fluorescent lights in his glasses. I asked about the weird music and he shrugged. “It’s on all the digital stations,” he said, as if there were nothing unusual about this. “I guess I could put a record on.”

At first, the music seemed to have a relaxing, even spiritual quality that some people might like while they meditated or fell asleep. But it quickly acquired a pressing monotony that bothered me. I heard waves and above them a deep, melodic drone that occasionally aspired towards tenor. The drone made me think of Gregorian Chants. Sizzling cymbals like fine grains being poured onto a metal roof added occasional variety. For a few moments, the sounds captivated me as I broke them down. Then a creepy sensation set in; I snapped out of my reverie and left the store without buying a record.

On my way out, the three kids dressed in black were heading in. I’d seen them around: the long hair, the studs, the chains, the tall boots and black jeans and Slayer T-shirts. They seemed too much on the Death Metal side of things for that shop. Too much on the Death Metal side of things for their generation, really. I’d never seen them say a word to each other and today they walked over to some speakers and just stood there.

Clouds had blotted out the mid-morning sun that had been shining earlier. The day felt hot and humid—for Fargo, anyway—and clumps of people meandered slowly along the sidewalk. I was wandering towards the train tracks when I heard a commotion—a car squealing to stop and a lot of people anxiously shouting questions.

I turned and jogged back, following the voices. About a block over from the record store, a gang of people surrounded a red Jeep Wrangler. In the spaces between backs and arms, I saw a bald guy in sunglasses hanging out a window.

He told me, “I started in Bismarck this morning and the radio was fine until I hit Jamestown.” He moved his head slowly along the half-circle of people surrounding him, as if reporting on a major event. “That was an hour-and-a-half ago, and it’s been this shit ever since. Almost put me to sleep—I gave up and turned the radio off. And I have regular radio, not Satellite like you’ve been talking about. I tried AM and FM. Nothing but that moaning.”

“Do you know what it is? What’s causing it?”

“Just because I started out in Bismarck doesn’t mean I know any more than the rest of you.”

I walked back towards the tracks. What a glitch to end all glitches, I figured. How the hell was it possible?

Just beyond the tracks lay long lines of businesses to either side of the street. I went to one called Peaceful Pizza, a hipster joint with peace signs and Sixties-Era hippies painted on its blue walls. I sat at the bar and ordered a beer. When the bartender brought it, I handed her a twenty and asked for a bunch of ones to use in the jukebox.

She had short blonde hair and always wore skirts with high heels—at Peaceful Pizza, go figure. She shook her head. “No use. Jukebox isn’t working right. Just plays this weird-sounding stuff.”

I looked over my shoulder at the machine. It resembled a glorified ATM with a neon-blue tube running along its arced perimeter. “Mind if I try?”

She laid a hand on my arm. “We unplugged it, Jay. The sound was—we just didn’t like it. Made me dopey.”

I gulped down the beer and headed outside. Some cars drove by and I could hear the music through their windows—the waves, the drone, the sizzling cymbals. A few cars stopped at a red light and I absorbed more of it. While listening, I thought of analog and digital and satellite broadcasts, of signals sent via air and cables underground. These channels surrounded us, wrapped themselves around us like pythons. If something—who knows what—wanted to reach us, to influence us in some way or tell us something, controlling all those networks would be a good way to do it.

I’d ended up staring at a break in the clouds wondering about all the signals criss-crossing up there. A young girl drinking coffee walked into me; she gave me a confused, forehead-pinching look and kept on walking. Some of her coffee had dribble onto the sleeve of my white shirt.

Instead of going to my favorite bar, located about ten minutes away, I ducked into a coffee shop. Inside, it was dark and cool and I again heard the sounds. Standing there enmeshed in that darkness, I felt how worshipful it sounded. I imagined men and women standing on daises and draped in long black gowns, arms raised in supplication, followers amassed below in various attitudes of devotion. Behind this scene, an ocean shoreline at twilight with one moon too many in the darkening sky.

This time I had to shake my head to snap out of it. I walked over to the counter, where the barista was sleeping, head resting against her fist.

I cleared my throat. The barista blinked her eyes and yawned. I asked if she could do anything about the music. She looked around confusedly—almost, I thought, in a half-panicked way. “Shit,” she said. “That’s weird. I thought I changed it to a CD.” The girl stared down at her hands as if she wondered if they still belonged to her.

I left to avoid the sounds. Outside again, the clouds had almost disappeared, and it seemed like the small crowds along the streets were thinning. Nothing unusual about that. It was a Saturday in June; a lot of folks had gone to the Lakes or down to Minneapolis for a Twins game. I took a left and found myself in my neighborhood, the Hawthorne area, where few homes had been built since 1930. Today, the streets felt empty in the way that streets can only feel empty on a sunny Saturday in June after most people have left town. I walked until I came to my bar, the flagship tavern of Hawthorne: Tuffy’s.

Inside, the darkness and cool air rivaled the coffee shop. I didn’t hear any music. Of course I didn’t: Tuffy’s had no source for music except the jukebox—an ancient one that played only the two dozen CDs it housed, and a good quarter of those didn’t work. Tuffy’s doesn’t even have windows—just two glass doors—so you can feel lost from the world once you go in there, and that’s what I usually needed, and what I especially needed at the time.

I had every intention of burying my face in a drink and pretending that the whole ordeal with the music had ended. Only two customers—both regulars—sat at the bar. Alice—Lighthouse Alice, Amazon Alice, taller than me when she wore the right shoes—sat frowning into her phone. Next to her sat Klondike, who’d joined the Army back in the Eighties and had ended up stationed in Alaska. He didn’t like cells, so he just frowned at the bar.

I sat down next to Klondike and Michelle, the bartender, came running over. Michelle got anxiety over reports of serial killings in Florida, so I knew that if she’d heard about Fargo’s strange broadcasting problems, she’d be manic. And she was. “Did you hear that damn noise?” she asked, and she asked a bunch of questions after that.

I told her it was nothing to worry about and she got me a Jack-Diet. After a few sips, I took out my cell and dialed up YouTube. I found Def Leppard’s “Photograph” and turned the volume up, but only enough so I could hear it by pressing the warm phone against my ear.

I heard the waves and the incantatory hum and immediately turned off YouTube. Everybody sat there without talking. I’m not sure for how long, but long enough for me to stare through the glass doors and watch traffic dwindle to almost nothing on University Avenue, two blocks over. Long enough for Michelle to bring me a second drink and then a third.

Michelle’s frustration climaxed and she tossed her cell onto the bar. “There’s nothing in the News about any of this,” she said.

“Have you heard anything we haven’t, Jay?” Lighthouse asked me. “My daughter says those . . . sounds are on every radio station. They’re even on the TV now. You get the picture, but then only those goddam sounds.”

“It’s the government,” Klondike said, dismissing the problem with the wave of a hand. “They’re practicing something. Or they fucked something up. Happens all the time. They don’t know what they’re doing. At least they didn’t when they were writing my checks.”

Michelle picked her cell back up and dialed a number. She stood in place, shuffling nervously from one foot to the other while twisting her disheveled brown hair around a finger. Her face—wide and friendly but worn with the tribulations of motherhood and bad ex-boyfriends and whatever the hell was happening today—grimaced as if she were in physical pain. She lowered her cell. “Luke isn’t answering.” She shifted from side to side more rapidly.

Luke was her son.

“This is the third time I’ve tried.” She seemed about to cry. “The third time.”

“Christ on a wafer,” Klondike said.

Alice scrambled for her cell and dialed. After a while she did it again. And again. Then she stood up, almost knocking her chair over. “I’m leaving. I’m going home.”

“I should too,” Michelle said.

A paralyzing stillness settled over us after Michelle said that; we fell into a silence so total it became tangible, a heaviness that pressed us down. For a moment, we waited, and that’s all we did. I imagined everyone in the world suddenly frozen in place, motionless as statues. I imagined that clouds no longer moved across the sky and the earth had ceased turning. And I sensed that we might remain standing there in Tuffy's forever, eternally awaiting the first soft clap of thunder from a distant horizon we’d never see again.

Then Klondike said: “That’s okay. Jay and I can mix our own drinks.”

“This isn’t funny,” Alice said, a whispered observation, drifting along the air like a single thread of spider’s silk. “Something’s happening. Something’s really happening.”

The two women started moving towards the door when the TVs came on, the whole ring of them that ran around bar. It showed the game in Minneapolis, but the only sound was the music. I grabbed the remote Michelle had left in front of Klondike and aimed it at the TVs, hitting the OFF button. Nothing happened. Michelle snatched it from me and tried as well but with the same result.

“Wow?” Klondike said. I think he spoke it as someone would a question.

Michelle angrily, emphatically kept pressing the OFF button while Alice started for the doors; I still remember her tall, wide-shouldered frame and neck-length black hair silhouetted against the door’s glass.

Then all our phones rang.

Michelle’s played a Pink song and Alice’s played some Joplin while Klondike and mine played the cheerfully generic factory setting and we all were as scared as we’d ever been. I think I can speak for the other three on that, even Klondike. They all started reaching for their phones and I screamed for them to stop: “Don’t answer. Goddammit. Don’t answer.”

“But it’s my kid,” Alice said.

“It won’t be and you know it.” I grabbed some cocktail napkins, tore them into bits, and started stuffing my ears with them. I told everyone to do the same, and they did, even Klondike. My hands shook so badly I kept dropping the napkins.

As we all stuffed our ears, the ground swelled under our feet, as if a wave were passing by beneath the building. Liquor bottles fell from the shelves behind the bar and over by the off-sale stand.

Brightly lit signs advertising beer and whiskey slid down the walls. “I’m going. I’ve got to get home to Amber,” Alice said. She left. Michelle followed.

Just after they disappeared around the corner, I heard a sound like a tree splintering in half and falling over.

“We shouldn’t have let them go,” Klondike said.

“Maybe we can stop them.”

We ran outside. The heat and humidity had become unbearable. I could hardly breathe; I felt wrapped in clammy woolen blankets that had been soaked in warm bacon grease. Michelle and Alice were driving out of the parking lot, side by side, when another groundswell occurred and one car smashed into another in a flurry of squealing brakes and crashing and screaming and car alarms.

There came a wailing that sounded at first like an elephant but then broke apart into the rattling growls of a giant wolf.

Klondike put his hands over his ears and shook his head like a dog surrounded by bugs. “Something’s coming. We need help,” he said. Before I had a chance to answer, he was running towards his truck. I saw one of the women—I think it was Alice—crawling out the passenger’s door of her car since the driver’s door had slid too close to the other car.

Klondike came stalking towards me with two twelve-gauge pump shotguns, one in each hand. He was a short, compact, muscular guy with skin the color and texture of beef jerky, and it struck me as entirely appropriate that he’d have two shotguns in his truck. He tossed one to me and I dropped it at my feet because my hands had become so sweaty. I heard him cussing me as I picked it up and then another wave pushed the ground up under our feet and we both fell.

I looked over and saw Alice on her knees, praying. The sky had changed color; it had become purplish. Then I heard a terrible crash as if a crack of lightening the length of South America had hit this world and split it in half. My ears went deaf. I looked down the blocks in front of me and saw a smoke-cloud rising over University. The smoke was so thick—black, expansive, and curling downwards on both sides at the top like a massive fountain of soot—that I can’t say for sure what I glimpsed inside it.

In my memory, I see a tree with incredibly long, thin limbs that moved on their own. As did the smoke cloud, the thing kept rising, so I never had a sense of its full height, although it must’ve been immense. Then Klondike started firing his gun from his knees. He managed to make it to his feet and was reloading when I started firing. I emptied the gun and fell forward. I had nothing left and I felt like the atmosphere was going to flatten me.

I glanced over at Klondike, hoping he could toss more ammo my way, but he’d dropped his gun in front of his knees and was staring into the concrete lot, unmoving, chin resting on top of his chest. He’d placed his hands flat on his thighs and had assumed an attitude resembling prayer. I looked behind him. Michelle must’ve been hidden behind one of the cars.Alice, meanwhile, still prayed, but to a different God now. Her joined hands hung in front of her and her face was almost parallel to the ground.

My thinking skipped a beat or two and I found myself also kneeling with bent head. Although my arms felt like wet concrete, I managed to reach one hand up to my ear: the shreds of napkin were gone. They must’ve fallen out in the commotion. The music—the incantation and waves and cymbals—was filling me, pushing out everything else, replacing thought and memory with its own hypnotic mastery. It needed no radios, TVs, or phones anymore.

Soon, only the music remained, intermingling me with the still rising monstrosity that I sensed without seeing. Maybe I saw it descending back into the ground before I became waves of music that rocked me into some kind of oblivion reminiscent of sleep but more like a complete paralysis of will.

I came to with Klondike shoving his foot into my ribs. I remember my relief when I realized how cool it had become—it had dropped all the way down to the mid-80s.

He also told me that the music had stopped.

Although so much remains murky, I distinctly remember the look Klondike had as he stared down at me. His eyes looked tired and knowing and his lips wanted to smirk but got stuck in a position more like a grimace. I think of it mostly as a sad acknowledgement. Sad because he knew we could never talk about this.

I go to Tuffy’s every day. I brood over my drink; Michelle pauses a moment, looks towards me. Her lips part a bit, then she shakes her head and walks away. Alice and Klondike and I, meanwhile, don’t sit near each other anymore. So I sit and think by myself, and I feel more miserable every day as I remember Klondike and me shooting at it. In its ancient eyes, I figured, we weren’t even worthy of the time it’d take to destroy us.

We were ungrateful.

No one outside Tuffy’s speaks about the events, either, except the crack in University and how they’ve heard of that happening before in other towns, just out of the blue like that, something to do with sinkholes. I think most people legitimately don’t remember much—they’d either been asleep or something close to it.

I did notice how, for a while, everyone wore a kind of sad, disappointed look, like they hadn’t received what they’d wanted for Christmas or their team had lost in the playoffs.

Tim V. Decker grew up in Central Maryland and attended college at the University of Delaware. After spending a large chunk of the 2000s in Wilmington and Philadelphia, he moved North and currently teaches literature at Minnesota State University Moorhead in addition to writing fiction. His work will also appear in Crypt-Gnats: Horror You’ve Been Itching to Read, an anthology by Jersey Pines Ink, Devil’s Hour, an anthology from Hellbound Books, and Switchblade Magazine.