On this month's Morbidly Fascinating Page:

The Influenza Pandemic of 1918

IN THE ARCHIVES:

Bog Bodies

Google Maps

Preserved

Last Meals

Utrecht Hospital

Dinosaurs to Birds

Ghosts of Alcatraz

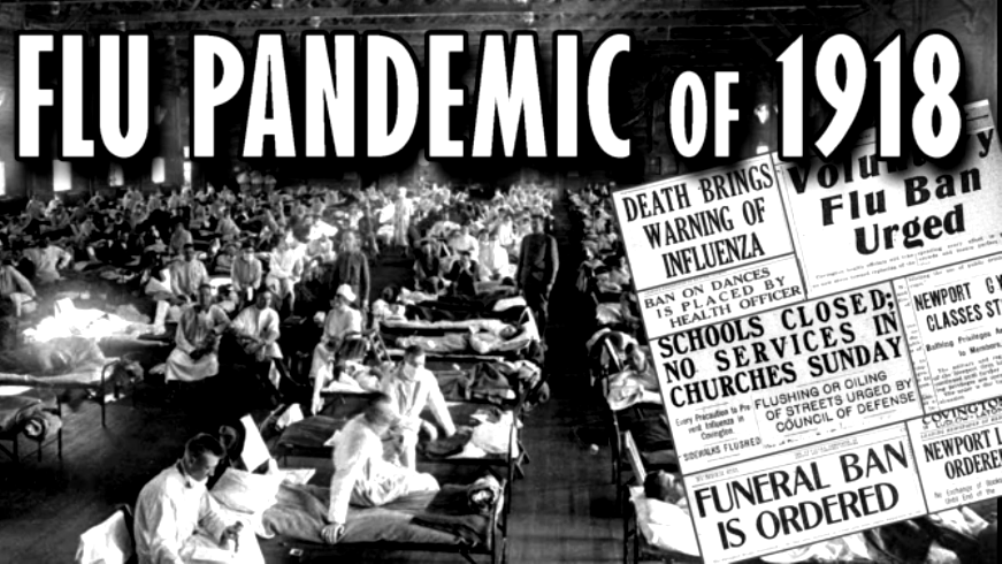

PHOTOS OF THE 1918 FLU PANDEMIC ARE BELOW

What strain was the Spanish Flu in 1918?

The 1918 flu pandemic, sometimes referred to as the “Spanish flu,” killed an estimated 500 million people worldwide, including an estimated 675,000 people in the United States. The strain was H1N1, technically a swine flu, but H1N1 is a human disease. People get the disease from other people, not from pigs.

The disease originally was nicknamed swine flu because the virus that causes the disease originally jumped to humans from the live pigs in which it evolved. The virus is a "reassortant" -- a mix of genes from swine, bird, and human flu viruses. Scientists are still arguing about what the virus should be called, but most people know it as the H1N1 swine flu virus.

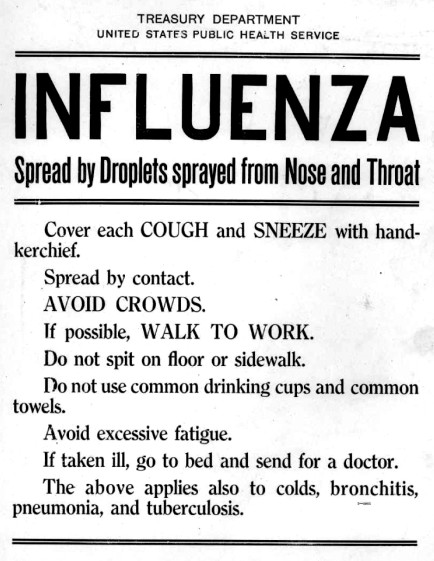

It must be remembered that in 1918, only bacteria had been discovered. Little was known about viruses at that time because the electron microscope was not invented to detect viruses until 1931.

What strain was the bird flu in 1997-2003?

In constrast, the flu that spread in 1997 and 2003 was an avaian (bird) flu, H5N1. Originating in Asia, H5N1 killed over 100 people worldwide.

What stain is COVID-19?

Coronaviruses are named for the crown-like spikes on their surface. COVID-19 is sometimes referred to as SARS-CoV-2. The specific strain is not yet available (there may be as many as eight sub-strains), although genetic testing is underway. Labs around the world are turning their sequencing machines, most about the size of a desktop printer, to the task of rapidly sequencing the genomes of virus samples taken from people sick with COVID-19. The information is uploaded to a website called NextStrain.org that shows how the virus is migrating and splitting into similar but new subtypes. You can see more HERE

Why was this flu at one time ignored by history?

For the first 50 years after the Spanish flu swept around the globe, killing about 50-100 million people, no one – least of all historians – gave it much thought, concentrating instead on the far more compelling story of the Great War. Indeed, in 1924 the Encyclopedia Britannica didn't even mention the pandemic in its review of the "most eventful years" of the 20th century.

This neglect of the "Spanish influenza" extended to the public sphere, hence the marked absence of memorials to the nurses and civilians, most of them young adults, who perished in the three waves of infection.

Why this should have been the case puzzled commentators at the time. "Never since the Black Death has such a plague swept over the face of the world … [and] never, perhaps, has a plague been more stoically accepted," commented The Times in December 1918, at the height of the deadly second wave of the pandemic.

One obvious reason for the silence about the flu was the way that the pandemic was overshadowed by World War I. People were told to focus on their patriotic duty for the war effort.

But perhaps the most important reason is that, unlike the soldiers who gave their lives for king and country, the flu dead did not readily lend themselves to narratives of nationalism and sacrifice. Instead, they became the forgotten fallen. There was pride taken in those that died in battle, and shame for those that died of sickness as civilians.

Still, it was the war that helped spread it across the globe. The war fostered influenza in the crowded conditions of military camps in the United States and in the trenches of the Western Front in Europe. The virus traveled with military personnel from camp to camp and across the Atlantic, and at the height of the American military involvement in the war, September through November 1918, influenza and pneumonia sickened 20% to 40% of U.S. Army and Navy personnel.

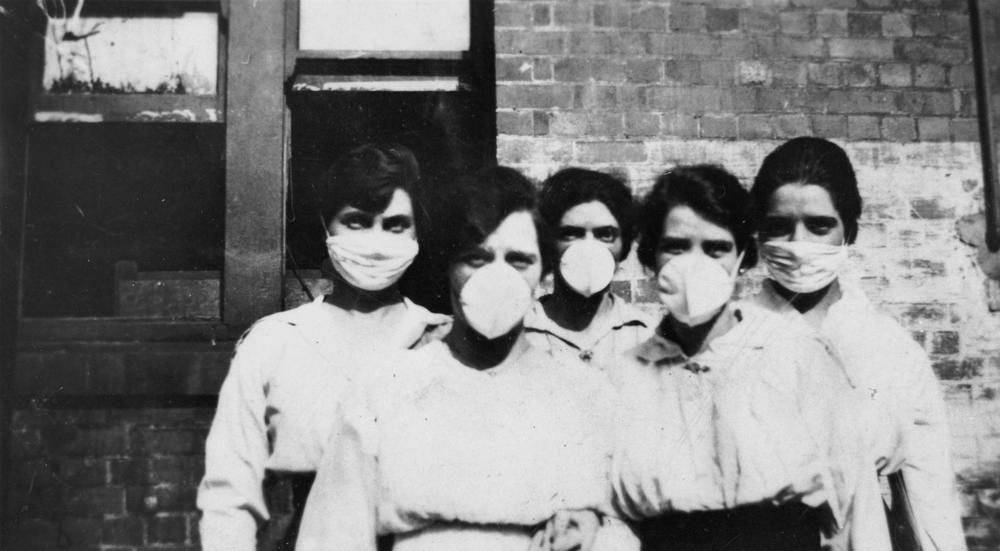

Above: Many American cities passed laws that citizens were required to wear masks while out in public. Members of the board of health at first advocated the arrest of any person appearing without a mask. This afterwards changed to a request that the police “send home” anyone violating this rule. Members of the board say they were advised that this action may legally be taken without special ordinance enacted by the common council.

Above: In the beginning, ambulances would take individual bodies away.

Above: After a while, public funerals were forbiddren in many states. Instead, mass graves were dug.

Above: In the beginning, individuals were comforted.

Above: After a while, individuality could no longer be possible.

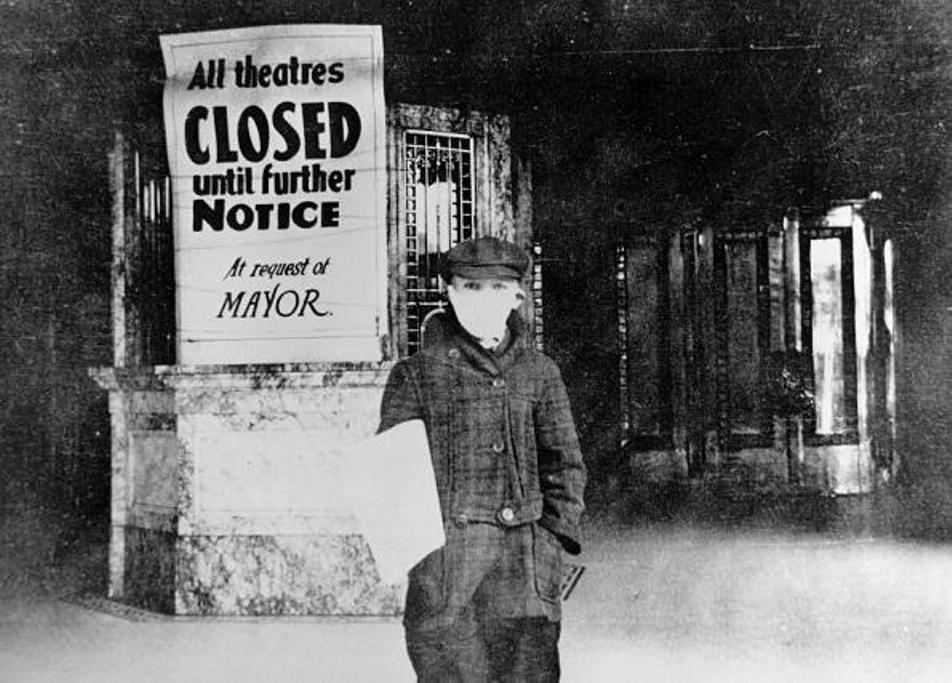

Schools were closed. Church services were banned. The federal government limited its hours of operation. People were dying — some who took ill in the morning were dead by night.

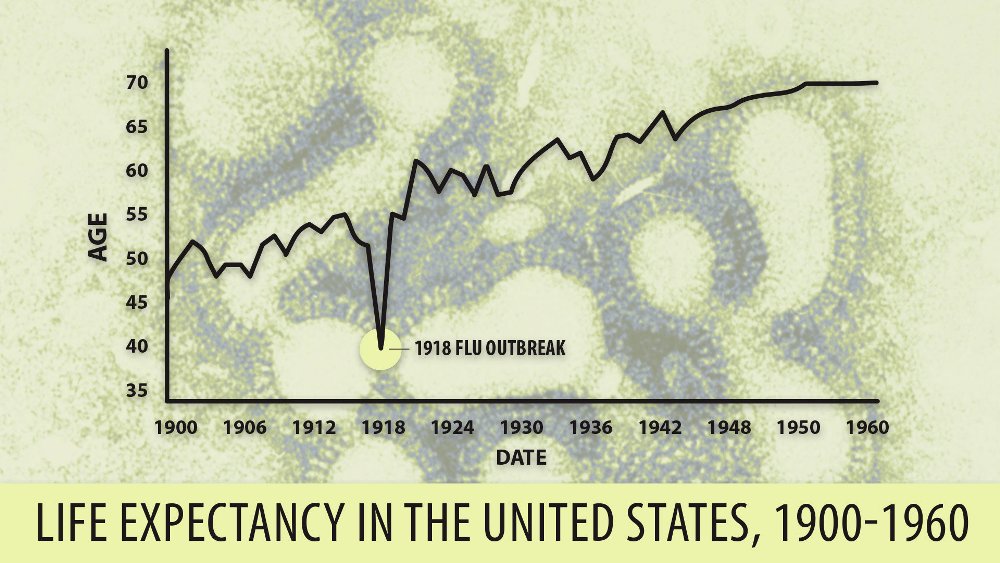

A shocking chart is below.

What was the Spanish Flu?

The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, the deadliest in history, infected an estimated 500 million people worldwide—about one-third of the planet's population—and killed an estimated 50 million to 100 million victims, including some 675,000 Americans.

Did it originate in Spain?

In reality, this flu possibly originated in Kansas, USA, although that has not been proven. However, the first cases of the outbreak were recorded in Haskell County, Kansas, and Fort Riley, Kansas, where young men were being hospitalized for severe flu-like symptoms.

Why was it called the Spanish Flu?

In World War I, neutral Spain was the first to report flu deaths in its newspapers, so commentators soon nicknamed the pandemic ‘Spanish flu.’ This flu did not originate in Spain, so the nickname is erroneous but it stuck.

How was the Spanish Flu different from COVID-19 (the coronavirus)?

As the wrath of COVID-19 continues to surge worldwide, sinking its teeth further into Europe and North America, scientists and historians are drawing parallels to the 20th-century influenza but are quick to point out that there are still stark differences.

While COVID-19 primarily puts seniors and immuno-compromised people at risk (at least, that is the assumption of the current coronavirus at this point in time), the Spanish flu targeted young, seemingly healthy young adults, mostly males.

Modern analysis of the 1918 Spanish Flu has shown the virus was particularly deadly because it triggered a cytokine storm (overreaction of the body's immune system), which ravaged the stronger immune system of young adults.

Modern hunt in Permafrost to study some Spanish Flu victims frozen in time

1997 -- Over the mass grave a tent with a special air lock has been stretched and inflated. The tent is for privacy in this somber enterprise and protection against letting anything possibly dangerous escape into the outside air. Inside, the diggers, with medical scientists at their side, will go about their business of opening the resting place of 1918 flu victims who were buried here 80 years ago.

This is a critical moment in one of the most ambitious efforts yet to solve an intractable medical mystery: What caused the influenza pandemic of 1918 and early 1919? Why was this particular contagion so virulent that it killed 20 million to 40 million people worldwide? Johan Hultin decided to find out.

A survey with ground-penetrating radar established that the bodies, side by side, were indeed in permafrost and thus should be well preserved for medical study. However, this proved to be true for only one body...the rest were skeletons.

Buried and preserved by the permafrost about 7 feet deep was the body of an Inuit woman that Hultin named “Lucy.” Lucy, Hultin would learn, was an obese woman who likely died in her mid-20s due to complications from the 1918 virus. Her lungs were perfectly frozen and preserved in the Alaskan permafrost. Hultin removed them, placed them in preserving fluid, and later shipped them separately to Dr.Taubenberger (USA)and his fellow researchers, including Dr. Ann Reid, at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.5 Ten days later, Hultin received a call from the scientists to confirm — to perhaps everyone’s collective astonishment — that positive 1918 virus genetic material had indeed been obtained from Lucy’s lung tissue.

See the article HERE