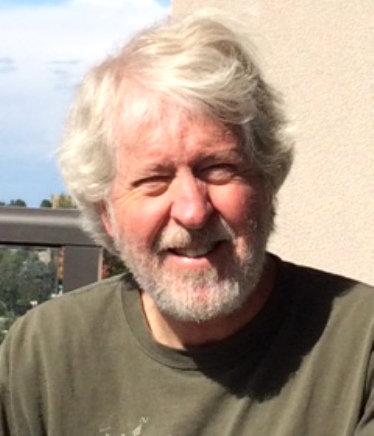

The February Selected Writer is Gary Robbe

Feel free to email Gary at:

grobbe53@gmail.com

NOT BURIED DEEP ENOUGH

by Gary Robbe

A scratch at the door. She shoots the son of a bitch dead, in the head and chest. Drags the body by the legs, grabbing there just above the muddy boots so they don’t slide off, drags the body to the porch and down the steps.

She takes a break. Smokes a cigarette. The wind lifts the smoke to the clouds and beyond and the humidity is godawful. Relaxed, sitting on his dead rump, drawing her knees up and sucking the smoke into her lungs holding and exhaling. Just relaxing. Two stars, three, popping out. Nobody’s business.

It smells like rain. Weatherman said a slight chance before she blew the television to smithereens. Henry’s ass is rock hard. She flicks the cigarette matching the lightning bugs. They

are all in love.

She got him, this time. Stopped him short at the back door, surprised him with his own 357, couldn’t miss so close even with the black strings that could be shadows could be anything but the light of day. The never easy tall man wearing shadows like his flannel shirt and rotten off the bone blue jeans more a filthy green who knows what snot he rolled in before he got here. This place. This man deserved to die. Again and again and again.

Bonnie lifts her head and looked above the house, not direct, not looking at anything anymore. A breeze lifts strands of hair off her nose and across her forehead, back where they belong. He was a mess. Coming after her the way he did. Always something.

Once upon a time she is oblivious, in the kitchen. He loves her chili. So she makes chili. He is far away, will never smell her chili again. She makes it for herself. Browns the ground beef and pork. Drains all but two tablespoons of fat. Adds garlic and onion, cook and stir until tender.

He lunges out of the wall, the blade slicing neat holes.

Add tomato sauce, water, beer, chili powder, bouillon, cumin, paprika, oregano…sugar.

Do I even know you…yes, I’ve seen your face. Your diabolical round eyes your straight line red mouth, corlander yes, cocoa, hot sauce. Mix well. Falling against the door, fighting for her life. Her life. She hears the blade enter her, doesn’t feel it, hears the tearing, like cloth. Think. Boil. Reduce. Simmer.

She is out in the country but she hears city sounds. Horns. Shouts. Babies wailing. Children mscreeching. Drunkards cursing. Laughter. The falling stink of the city curtains, no small bowl this. Stirring cornmeal, flour, warm water. Warm water flowing out of her.

Not again. She drags the body across the dirt and high grass of the unkempt lawn. To the edge of

a woods. Leaves the body there in a soft blanket of dark where the stars can’t reach, ever, runs

back to the house to the garage and grabs an old rusty shovel.

Stir the meat into the chili and cook, covered, an additional twenty minutes. Roll back white eyes.

With the shovel she breaks ground. My name is Bonnie she says to herself. But Mary is there with her, Elizabeth too. Annie is behind them saying soft things tinged with hate. We are Bonnie.

We are broken. The warm Texas night syrup, dark and delicious. She knows this scene oh too well. Horse hoofs clattering on brick, footsteps, millions of footsteps, voices intermingled as one, loud, harsh from lifted lights, worms working their way up, indeed, loosening the soil, helping her. Breaking her. Fog. Rich and accepting—sweepy fog.

She digs. The shovel is heavy and the earth is hard in places, roots she thinks, and she chops at it

with all the strength she has left. Then on her knees, scraping with her hands, pushing dirt aside,

sweat splattering off her or maybe a light rain now, the few stars gone. Catherine, someone says.

An introduction she hears as clear as the wind rattling the branches nearby.

Voices, hands, many hands around her—she senses this because her eyes are closed, not wanting

to see. The voices chatter in thick accents and she can’t decipher a word of it. But they are with

her. They give her strength

Deep enough. She rolls the body into the shallow pit. Handfuls of dirt, sprinkled like seasoning. Then she shovels the loose dirt onto the body and around the sides, patting it lightly with the backside of the shovel. It takes a long time and the rain is stronger, tympanic against the leaves and grass. The voices are gone. They will be back.

Bonnie rubs her wet arms. Stretches. Walks back to the house and takes the shotgun resting on the kitchen table like a broken trail of smoke, brings it back to the fresh grave. She unloads two blasts into the soft mound of dirt. “Damn you, Henry,” she says. I will break you.

Stir the chili. Taste. Repeat. Saucy. Saucy Jack.

The lights are out. She sits at the table in the dark, waiting. There was a man, once, she knew. Tall and strong, he liked to hurt her in quiet, secret ways. She ran from him but he always found her, no matter where or how far. She tries but can’t picture his face. Could she ever picture it? What did he ever do to you, really? Mary asks. Or is it Elizabeth? He grew old, Bonnie replies, scuttling about the kitchen.

The house is small, six rooms, a cabin miles from nowhere. There are trees everywhere that muffle sounds from the distant roads and neighbors. She paces each room patting the blood-stained walls stepping over the remains of his dogs, remembers him at the bathroom sink in the morning gargling in such an irritating way, not knowing where he was, who he was.

The coffee is cold but she empties the pot into flowery cups that are set on end tables, blanket chests, the fireplace mantle. In case her guests are thirsty.

She caught him by surprise in the morning, caught him before he caught her. Oh, she knew who he was, a hundred years removed, and her friends laughed that she used a knife, at first. The dogs barked like crazy. Didn’t like her dragging him out, holding on to him with their teeth until she took care of them too. She put him in a shallow hole where a garden might someday be.

He came back. Surprised her in the living room, coming up behind her, and if it wasn’t for the shrieks of Catherine and Elizabeth…well, he was old and dead, moving so slow she was able to hit him in the head with a the fireplace poker. She let him lay there for a while to catch her breath, then grabbed him by the feet and pulled him back out to the fresh dug up spot and put him back. She was drenched with sweat. The house was hot with the windows closed, but she had to keep them that way. There were enough flies in the place as it was. And she didn’t want him trying to climb through the open windows.

All day long she kills him, the empty-eyed monster. She has buried him too many times to remember. There are fresh mounds all over the yard. The voices worn on her head like a tight- itting wool cap. And the heat is so damn oppressive. Why does she have to make chili, on all days when it is so hot? His favorite dish. All those years sitting next to him, sitting across him, lying in the same bed but never once really touching, not knowing the secrets hidden in that black mind of his.

The wood floor is slick. Henry’s gray hair a buzz to the empty space leading to the hall. She fires

three shots into the space blasting bits of plaster and wood where he once was. She takes one of

his knives and scratches it along the wall until it reaches a painting of a smoky city, rips through the buildings and chimneys and blue clouds. All the blue clouds.

Stay down, Henry, she says.

Bonnie locks the door, checks it a minute later to be sure. Locked. Unlocked. Locked. She can’t remember. She is bone tired. There was a man once. Henry. Not his real name. There was a man once…

She prays it is over this time. Closes her eyes and voices scream in her head. We hope he is in the ground for good. We hope.

The man has been killed a thousand times in her head. Over the years she has stabbed him, set him on fire, shot him with practically every handgun and rifle the man owned. Henry has a crossbow. She used to picture the arrow clean through his evil heart. Thirty something years together and it was the only thing that made her smile.

The voices convinced her who he really was. The soul survives and moves on and even though he petted the dog and never took a hand to her she knew—she knew—what was lurking beneath. Everything made sense then, why she hated him the way she did, why the very picture of him in her mind made her sick. It was only a matter of time before he let loose on her the way he did those unfortunate women in London.

I did this for you, she says. Turning this way and that. It is so hot to be cooking. The pores of her skin are steaming and her black dyed hair is coiled wet like a medusa dream. She whimpers running through the house, spinning and dropping to her knees to pray and look for the crossbow under the bed. Not there, she shoves the hallway closet door open and rummages past shoes and stacked boxes, jackets and wrinkled coats, listens to make sure he isn’t working to get in the house again. What did he do with it, and how do you use it anyway?

Plug an arrow in and shoot at the target. Simple. Have to find it. Used up all the bullets glancing at the pockmarked walls and ceilings.

It occurs to her to just leave this place, the man in the ground. Leave everything behind. But she

can’t do it. Voices brought her here, voices keep her here. Mary, Elizabeth, Annie, Catherine. She hears fresh voices soft and delicate, feathers of death. She looks at the raw and broken blisters on her dirty hands, the dried blood, his and hers on her blouse and pants.

So much to do…

The chili is on the stove. She has bowls out on the table now. The guests will be hungry. She hears their voices, knows they are still around. The man in the shallow grave stirs and whispers and shrugs against the soft earth while the voices strong drown his cries outside.

Outside.

Staring at the empty bowls and the empty shotgun and the empty pistol what did she do with the shovel dragging her legs under her on the chair in the dismal light. Doesn’t matter where she is,

farm out in the country or loud fog shrouded city with broken lights and cobbled stones and dreams.

There is a scratch at the door. She is sure it is him. Dead sure.

Gary Robbe is a retired educator living in Colorado, where he spends his time writing and playing in the mountains. His work has appeared in The Horror Zine, Aphelion Webzine, Sanitarium Magazine, Cheapjack Pulp, and Deadman's Tome, among others. He has had stories in several anthologies, including Shrieks and Shivers from the Horror Zine and Deadman's Tome March to the Grave.