The August Featured Writer is Rachel Coles

Please feel free to email Rachel at: rachel.coles1@gmail.com

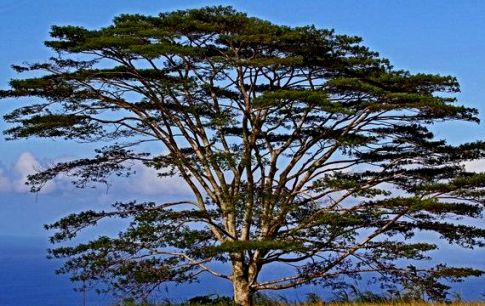

THE KOA TREE

by Rachel Coles

Dana Egbert, unlucky on-call worker for Maui Child Welfare Services pulled the rattling state car off Makena Road onto a dirt track between Big Beach and Ahihi Reserve, looking for a hotel that didn’t exist on Google Maps. There were a lot of places that didn’t exist on Google Maps on Maui, and she’d been to a lot of them in her investigations, so she just hoped there was something useful at the end of this one.

She had already been awake for over forty-two hours with another case. She had finally been headed home when Intake had called her. Sheri, the Intake worker had been shaken after she’d taken the call. She was never shaken, at least not when anyone else could hear. She had called the police to meet Dana there.

A kayaker, Mark Bledsoe, from Chicago, had been out past dusk on the bay looking for dolphins and turtles. When he’d turned to shore, he’d seen a girl in his binoculars in a white dress with a bloody face wandering the rocks in front of a hotel, and a little boy following her. He was dressed in formal Victorian-looking clothes.

No one really came out this far toward the lava fields after dark, except tourist kayakers who didn’t have the sense to come in shore before dark. There was no reason a child should have been out here alone. But what had gotten Intake to react with alarm was his description of the girl. According to his account, her face had been pulverized until there was nothing left but holes, blood and tissue. When Sheri had tried to get more details, she had heard a splash before the call went dead. They both hoped he had just been drunk and dropped his phone in the water.

The sparkling of the sapphire and cherry lights of the police and EMS cast eerie shadows in the trees around her as she parked. There were two cruisers, and an AMR ambulance in the lot, which made her feel slightly more secure. She parked in the dirt lot, switched her phone light on and picked her way through the candlenut and autograph tree pods littering a path down to the ocean.

She usually liked the sound of the waves, but she didn’t tonight, not here. Here, anxiety nibbled at her brain like sand crabs, and washed through her every time the waves crashed. You’re not welcome here, they whispered. There were places on the island like that. Though no one ever welcomed Child Welfare, this felt like an older hostility.

On the right, loomed a building that could only be called a resort in a real estate slum lord’s generous imagination. It was a dilapidated two-story plantation style building that had a sagging shingle roof, and two rows of four sliding windows that dated back to the 1960s. Its pale walls were mottled like a rotten tooth. When she went around the front toward the sea, the columns tilted as the wood of the porch cracked under the shift of sandy soil. Both the brush and the sea had encroached farther toward it than when it was built, and there was a rocky strand about five hundred feet wide to the high-water mark. In another five years, the sea would be at the front door, which was a black wooden rectangle hanging open half-off rusted hinges.

“Hello?” she called, wondering where the officers and EMTs were. She stood on the sand, waiting, wondering if she had missed them back at their cars. Maybe they had gone around the other side of the building. But she didn’t hear the rustle of brush, so she went down toward the water.

There was a kayak pulled up on the sand near a cluster of lava rocks. It was empty, but the size eleven footprints went from the wet sand and disappeared into the water. There were other tracks leading to the house, she realized, as her vision adjusted to the dark. The sand was seething around her. She yelped and leaped onto a pocked black lava rock. Small pale crabs emerged as if they were forming out of sand grains. Two ragged lines of them marched up toward the house.

She had always found crabs to be worrying. They were cute in the light, but in the dark, their motion sideways was too much like spiders of the sea, ancient and alien. These were ghostly white, phosphorescent and beautiful. She’d never seen crabs travel in such purposeful lines, as if organized by a hive mind.

She stood on the rock and peered north and south along the thin beach to see if the officers were there, but it was deserted. As much as she didn’t want to, she went back toward the house, wondering if they were inside and they just hadn’t heard her.

The house was silent, and there was only the flicker of car lights from the parking lot. From where she stood, she could see sandy bootprints on parts of the wooden porch that weren’t broken or rotten through. Only the glowing crabs marched in.

Inside that door was the last place she wanted to go. Ten years in social work had given her stomach an evolved sense of Get the hell out of here. And the warning voice in the back of her head was screaming at her that this was wrong, and raising the hairs on her neck.

But somewhere here, if it hadn’t been a drunk dial, there was a savagely injured child. She tried calling the police dispatch number to see where the officers were since she couldn’t reach them directly, but the phone showed no bars.

She growled to herself and went back up toward the emergency vehicles to see if she’d missed them. Behind her, she thought she heard the weighty tramp of police work boots, but when she turned around, no one was there. And the cars were still empty. The radios in the vehicles were eerily silent. She wanted to wait there for them, but the memory of the last time she had stood in front of an abandoned building bubbled up unwanted in her mind.

The suicide nine years ago had made the Minneapolis evening news. Someone had called in a tip about a kid on the Missing and Exploited Children site, her case. He’d been runaway and out of contact for two months, after being released from the adolescent unit of the local hospital. She had waited for the police to bring him down from the abandoned apartment building, so she could take him to the ER for assessment. But she identified his body instead. The last time she’d talked to him, he had called her on her work cell the day before. The call had crackled with connection problems, and then dropped. And she couldn’t reach him again. She didn’t know where he was until the tip. He had been wearing a purple Vikings shirt when he’d been found. She never wore purple anymore.

And as if her nightmare were coming to life, a figure appeared suddenly in one of the first floor window sat the side of the house, closest to the front, splayed as if it had either thrown itself or been thrown against the window. As quickly as it had appeared, it withdrew into the darkness. For a second, it had looked like a young girl, and an imprint of dark fluid was left on the glass where her face had been.

Despite the twenty pounds she’d gained on the job, she belted down the path, scraping her legs on kiawe thorns long enough to impale Jesus, and around the corner to the porch. She ran through the door as fast she could. Her exhaustion and nine years of self-flagellation erased the safety training from her mind.

Her breath was loud in the quiet of the parlor and hall that yawned ahead of her like a cavern. The water-stained wainscoting looked like bleached ribs, with cables hanging down like snakes. The glow of her phone made them move, slithering down the walls. The ghostly crabs marched past her feet down the hallway. But she couldn’t deal with that right now.

The moldy white wall to the left of the suite door made her sneeze as she backed against it, as she realized that bursting into a building where there might be an assailant as well as a victim wasn’t the brightest thing she’d ever done.

When she peered around the door into the first suite, the grey dim squares of the two bedroom windows were empty. The only motion was the oscillations of the red and blue emergency lights, bleeding onto the walls from the dirt lot outside. She crept across the warped floor to the bathroom. The holes where the scavenged toilet and sink fixtures used to be gaped like pulled teeth. Nothing moved except the shadows in the light of the phone. The emergency service call still didn’t go through.

Her heart thudded, sounding like drums in her ears over the muted surf. She listened for anything closer, a soft shuffle of feet. Where was everyone? Where was the figure she had seen in the window?

She went to the window. The dark smudge of blood looked like a Rorschach inkblot, confirming her sanity. But it meant that there had been someone terribly hurt, and they were still here. And maybe so was their attacker.

She knew she needed to leave. She knew she had made a mistake running in here, and it was a rookie mistake. Every shadow was a threat. But she froze, not wanting to reveal her location more than she already had. As much as she hated the dark in that moment, she shut the phone light off, so she wasn’t a beacon.

Total darkness enveloped her. It shouldn’t have. The ambient moonlight and emergency lights that had been reflected on the pale walls of the bedroom were gone. Even if the lights had gone off, and a cloud had covered the moon, there should have been a little light, and a darker rectangle where the door was. There was no light at all, like the inside of a grave.

She started hyperventilating as she fought panic. She swiped at her phone screen with shaking fingers, but it didn’t respond. The battery was low, but it wasn’t that low. And she realized that in her fear, her fingers were like ice, and she was shivering uncontrollably. It must have been eighty degrees outside and humid, but the room felt as if it was buried in Antarctica.

The inside of her felt frozen and hollow. The phone couldn’t be activated by her finger heat, because she didn’t have any. It was just a stress response, she told herself. She blew on her fingers, but nothing happened when she touched the screen.

She swallowed, frustrated at how stupid her predicament had become. Of course there was a door and windows. Her eyes just hadn’t adjusted. But as she felt out with her fingertips for where she knew the cold pane had been a moment ago, she felt only the rough scaly paint that felt more and more like crumbling dirt.

Suddenly, panic closed in and it seemed as if the air had run out. She stumbled across the room toward where she knew the door had been and encountered only wall. She slid down to her knees, gasping, resisting the impulse to scream for help because someone very hostile was here. Instead, she felt along the whole floorboard for the door, but there was none, anywhere.

She knew she was completely turned around, but she didn’t know which way she had been turned. As she went along, she could have sworn that the rotted plaster under her hands formed knots of volcanic soil, and that the room spiraled into the center as the walls got narrower around her.

Finally, her cell phone shattered the silence, as ‘Everything is Awesome’, the theme of the Lego Movie, played absurdly. She’d chosen it because it never failed to get her attention. She jumped as she looked at her phone screen. The number was Restricted. It must be the police.

She swiped at it frantically, praying it wouldn’t go to voicemail. She breathed and breathed on the screen until it was wet with condensation, and then swiped, pressing as hard as she could. It connected the call. But there was only an odd crackle on the other end, like a bad connection. The same kind of bad connection that had dropped the call from the suicide nine years ago.

“Dammit!” she yelled. “Hello? Can you hear me? Hello?”

The grey light of the phone should have lit up the room at least a little, but there was nothing beyond the glow against her hands, as if nothing outside it existed.

She crawled back and forth in the oppressive darkness, trying to change the reception. The static finally stopped. There was silence for a moment, then a rattle like someone trying to form words through water, like someone drowning in their own fluid. She’d heard a sound like that coming from Gran’s throat when she had visited her in the hospital, when she’d been five years old. Dana had been rushed from the room, but she had heard the sound, under the beep of the machines keeping Gran alive and the wail they made when she was gone.

Dana knew, with a freezing chill in the close warm air, that whoever was making that sound was in serious trouble. She tried to understand the words, but they degenerated into rasping, and then a soft whimper full of despair.

She pleaded, “Hello? Can you tell me where you are? Can you help me find you?”

She was answered by a wet burble, someone struggling to breathe on the other end. Tears ran down Dana’s face as she lay down on the dusty floor with her phone to her ear. She controlled her breathing, and evened her voice out as she spoke, “Please help me help you.”

The silence stretched for another few moments with her on one end, and whoever was suffering on the other end. Maybe whoever it was couldn’t answer; all they could do was listen. “Okay. If you want I can talk. Or I can just be quiet so you know I’m here.”

In truth, she wasn’t sure who was the one doing the helping. Even suffering, the person on the other end held her sanity together: the only connection to the outside world from her strange isolation, and her whole reason for keeping her shit together. Because someone needed her. Part of her desperately wanted to talk so the stillness of the place and the labored sounds on the other end didn’t swallow her. But her voice was too loud in the hush. And she might miss something vital that could tell her who or where this person was. So she just stayed on the line, trying not to drop the call.

Every so often, she would check in, “Are you still there?”

A snuffle sometimes told her they were. She sat on the quiet line for a while, tied to someone who couldn’t talk. At one point, she glanced at her phone. The clock read 3:33AM. Somewhere, between the time she’d gotten there and now, she had lost six hours. And at 3:33AM, the call ended.

She put the phone down next to her, laid her head down on her arms, and sobbed in despair. A scraping sound finally reached her ears, like the sound of fingernails on earth. She looked up, and the darkness wasn’t absolute anymore. It was dotted with tiny jerking blips of light. She squinted, and finally made out that they weren’t floaters in her eyes. They moved like the crabs. There was a phosphorescent stream of them now, like a glowing river along a black mirror.

She pushed up to her knees and slunk along the floor toward them, until she realized suddenly, that she wasn’t on wooden floor anymore. She had left the house, and the darkness was full of damp vegetation and the stinging bite of mosquitoes. The cars and lot and road were long gone, and she crawled across swirled lava rocks like alien glyphs lit by the silver moon, until her knees left wet burgundy prints. Still, the trail of white crabs skittered, moving ever forward.

She rose and stumbled into thick brush as the terrain rose, swishing through nehe and pili grass, through thickets of rough-barked trees, until finally she came to the remains of an ancient grove ofkoa trees, fallen, rotted, and overgrown with other vegetation.

The crabs flooded into the soil at the foot of one of them, a massive cracked stump, with the earth underneath it hollowed by its collapsing root system. She was wracked by pain from her trek, and she shuddered at the crabs that still brushed past her. But she knew now that the answer to whatever had happened tonight was where the crabs were going.

She slid toward the depression, feet first, her sandals ragged and covered in dust. The soil slid, and she screamed as it dumped her into the small chamber made by rain and roots. The crabs swarmed around and through every open space. She bit down on a shriek and tried not to vomit.

Something stuck out from the hard-packed volcanic earth still trapped by the dissolved root fibers. It was a human long bone. She knew that she needed to climb out and walk until she found the road, however many miles away that was now. She knew what stuck out in front of her was evidence of something. But it was like a magnet. The rasping breath on the other end of the phone still echoed in her ears.

As soon as her fingers touched the remains, she saw the past.

A young girl beat taro for poi in the woven rain shelter that stood where the resort stood now. She pulled at the neck of her uncomfortable sweat-soaked white dress. She looked as annoyed as any pre-teen Dana had ever seen.

A tall European man in a grey suit and cravat stepped through the brush, weaving as if he were drunk. He pulled along a little boy of about six, dressed similarly to him, but with thick black hair combed into sharp waves against his scalp. Still a few wisps escaped, giving him a mischievous look matched by the angry pout on his face. The man pushed the boy toward her. “Your brother is incorrigible! He was stealing fruit again!”

“That fruit is ours!” The boy yelled in English. His hot angry eyes met hers and his lower lip trembled for a second, but his jaw set the same way she saw in most of the warriors’ faces. He planted his sturdy little arms on his hips, and spoke to her in Hawaiian: “I got breadfruit for Alika. He has a new sister—“

The man interrupted. “Speak English!” He cuffed the boy on the back of the head.The boy stumbled to his knees, but leaped back up, and swung around and planted a fist in man’s stomach. The man doubled over, and then snarled and backhanded the boy across the face into the taro. He grabbed the boy by the shirt and hauled him to his feet and dragged him away by his hair.

The girl screamed “No! Leave my brother alone! Please!” She grabbed the man’s shoulder, trying to pull her brother away. He pushed her back and kicked the boy in the ribs. He screamed and fell to the ground.

The girl leaped on the man’s back, squeezing her arms around his head and biting his ear. Blood ran down his neck as he roared. He scrabbled at her and pried her fingers loose. She tumbled to the ground. She lashed out with her legs and kicked him. He stumbled, but recovered, seized the pestle she had been using and was on her again in a second. Then he reached for the boy.

When it was over, the man looked at what he’d done and a brief look of horror crossed his face, and then he swiveled his head around to see if there had been any witnesses. He dragged the bodies away to the grove of koa trees that looked like every other grove to him, and buried them, unmarked, scarring the roots with his mattock.

Dana came back to the present. She sobbed and pulled her hand away. “I’m sorry.” The crabs had ceased their strange swarming and were now acting independently again, climbing out of the space and away through the forest, a million solitary exoduses toward the shore.

*****

The bodies of two children, a young boy and girl, had been found and analysis pointed to their burial perhaps a hundred and fifty years ago under a koa tree deep in the forest. The Maui Police Department Forensics, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, and Department of Land and Natural Resources were working through records to identify them and find their family.

She didn’t know why she was the one to find them, or if it had been her special reprieve to get that phone call, a chance at a do-over to make up for someone she’d failed.

She thought of the crabs and remembered from her encounters with Hawaiian families that animals and plants could be aumakua, guardian ancestors. Maybe she hadn’t been the only one that night trying to salvage the past. She sent silent thanks out to them if they were listening.

She wondered if the call she had gotten nine years ago had been from the dead boy. Dana saw them all sometimes, in the abandoned resort in her nightmares.

Rachel Coles currently lives on Maui with her family. She works in child and adolescent mental health. During the COVID19 stay-at-home order, when not teleworking, she enjoys writing, binge-watching every sci-fi show under the sun, learning how to make her own yeast, turning a black thumb into a gardening thumb, and mutilating lovely Persian food recipes in the kitchen. She also enjoys the tyranny of her athletic daughter who has designed workout regimes for the whole family.